This article is written by Joachim Beck for the webite Taylor & Francis Online.

As part of European integration, the interaction between different administrative levels has become more intense over years. Accordingly the concept of the European Administrative Space (EAS) has been gaining increasing interest from both academia and practitioners

ABSTRACT

Going beyond a classical vertical multi-level perception, and focusing on the unsettled transnational patterns of inter-administrative cooperation in border-regions, the article suggests understanding approaches of institutionalization, taking place within the context of European territorial cooperation as an integral horizontal dimension of the EAS. Based on empirical findings that evidence by what patterns such horizontal institutionalizations in the field of European cross-border cooperation are characterized, the article develops a classification for the different forms of territorial institutionalism and suggests a set of intervening territorial variables, complementing established independent variables of neo-institutionalism in order to differentiate further analysis. As a conclusion perspectives of research are developed that may allow to better capture the diversity of forms of European territorial institutionalism and to recognize the role that cross-border territories are playing for the embellishment of the European Administrative Space.

1. Introduction

As a result of the process of European integration, administrative interaction between the national and the European level has become more and more intense over the years. Both the design and the implementation of European policies today depends on collaborative working relations between the historically evolved national politico-administrative systems of member states and a supranational government system under permanent evolution and change. Against this background, the concept of the European Administrative Space (EAS) has gained increasing interest from both academia and practitioners. Originally directly linked to the notion of an increasingly intense integration of a European government-system, and thus assuming and predicting a process of increasing convergence and harmonization of the different national administrative systems towards a more unified reference model in Europe (Olsen 2003; Siedentopf and Speer 2003), it has constantly evolved over time, and is now discussed in the light of a broader perspective on European governance.

Although the term is used frequently, the very definitions of EAS in the literature are addressing quite different things: From the dimension of joint values some see the EAS as a “harmonized synthesis of values realized by the EU institutions and Member States’ administrative authorities through creating and allying EU law” (Torma 2011, 1); others perceive it from the dimension of joint action as an “area in which increasingly integrated administrations jointly exercise powers delegated to the EU in a system of shared sovereignty” (Hofmann 2008, 671), stressing issues such as the “coordinated implementation of EU law and the Europeanization of national administrative law” (Hofmann 2008, 662), or the creation of a “multilevel Union administration” (Egeberg 2006). Further arguments refer to the dimension of participating actors and focus on the emergence of a more and more differentiated European multi-level governance (Kohler-Koch and Larat 2009), or suggest the “distinction between the respective constellations between supranational and state actors” (Heidbreder 2011, 711), hereby developing a conceptual focus with regard to the relationship between the governing and the governed, thus pleading for a combination of the dimensions of policy instrumentation in the EAS with the actor constellations and Europeanization mechanisms (Heidbreder 2011, 711–4).

In addition, and with regard to administrative law, Sommermann (2015) refers to the procedural dimension and differs between a process of direct Europeanization (both at the level of substantive administrative law, procedural administrative law, or administrative organization law) and a process of indirect Europeanization (functional adaption of administrative norms and procedures in relation to the cooperation principle, spill-over effects from EU-law into other national law domains and adaption due to the competition phenomena of an increasing trans-nationalization of administrative relations). Ultimately, and in the very dimension of further analysis, Trondal and Peters (2015, 81) are suggesting a “EAS II” concept, which takes the multi-level approach and the idea of loosely coupled inter-institutional networks (Benz 2012), performing tasks jointly, as a starting point and propose capturing the very role of the EAS in the European integration of public administration by studying its empirical emergence with reference to the broader concepts of institutional independence, integration and co-optation.

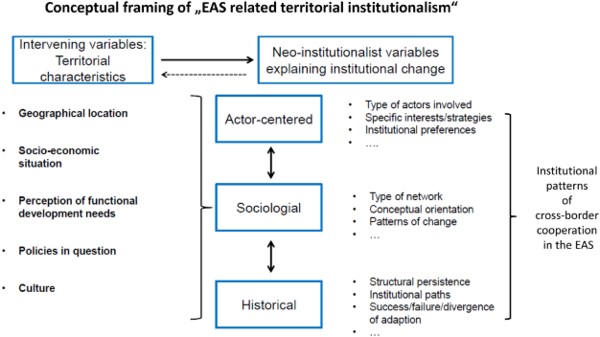

The dimensions cited above are de facto interrelated, suggesting that the EAS is both influenced by and contributing to European integration. The basic questioning here is to what extent the EAS represents an institutional capacity to support both the design and the implementation of European policy-making. This question in turn refers back to the more fundamental consideration of the functions, institutions are generally fulfilling within the context of public policy-making. Institutions can be understood as stable, permanent facilities for the production, regulation, or implementation of specific purposes (Schubert and Klein 2011). Such purposes can refer to social behavior, norms and concrete material or non-material objects. From the point of administrative sciences, institutions can be interpreted as corridors of collective action, playing the role of a “structural suggestion” for the organized interaction between different actors. The question of the emergence and changeability of such institutional arrangements in the sense of “institutional dynamics” (Olsen 1992) is subject of the academic school of neo-institutionalism, which tries to integrate various mono-disciplinary theoretical premises. Following Kuhlmann and Wollmann (2013, 52), three main theoretical lines of argument can be distinguished here: Classical historical neo-institutionalism (Pierson 2004) assumes that institutions as historically evolved artefacts can be changed only very partially and usually such change only takes place in the context of broader historical political fractures. Institutional functions, in this interpretation, impact on actors, trying to change given institutional arrangements or develop institutional innovations, rather in the sense of restrictions (path-dependency). In contrast, rational-choice and/or actor-centered neo-institutionalism (March and Olsen 1989; Scharpf 2000) emphasizes the interest-related configurability of institutions (in the sense of “institutional choice”); however, the choices that can realistically be realized depend on the (limited) variability of the existing institutional setting. The sociological neo-institutionalism approach (Edeling 1999; Benz 2004) in turn also basically recognizes the interest-related configurability of institutions, but – thereby rejecting the often rather limited institutional economics model of a simple individual utility maximization of actors – puts more emphasis on issues such as group-membership, thematic identification or cultural adherence as explanatory variables. When analyzing institutional dimensions of the EAS as dependent variable, it can be promising to refer to such neo-institutional assumptions as independent variables, in order to explain the shaping and specific characteristics of identified institutional patterns.

Three gaps can be identified when evaluating the current state of research on the EAS. First, beyond the scientific literature on European spatial planning (see e.g. Jensen and Richardson 2004), most reflections in Social Sciences on the institutionalization of the EAS follow an exclusivly theoretical understanding of vertical European integration, distinguishing between national and supra-national government-levels and studying the vertical interactions, interdependencies and mutual impacts between domestic and European corporate and/or individual administrative actors. The aim is to analyze to what extent an as yet still recent new additional administrative layer, directly linked with the process of European integration, has been developed at the supra-national level and how this impacts back on historically developed administrative systems. This vertical thinking, however, risks ignoring patterns of inter-administrative cooperation that have emerged at a horizontal e.g. transnational level: administrative actors – both at member state and sub-national and/or local level – are increasingly cooperating directly with administrative units from another (neighboring) state. This in itself represents a significant institutional pattern, which, as I will try to demonstrate below, should better be included in a holistic understanding of the EAS. Following the very theoretical foundations of governance-concepts (Benz et al. 2007), which cover both dimensions, such a horizontal dimension could lead to a complementary view and understanding of the vertically and horizontally differentiated nature of the EAS – a dimension, which is often not covered properly by the prevailing leading literature on European multi-level-policy-making, which limits the horizontal dimension of the EAS to the study of inter-institutional constellations within level-specific administrative systems which are themselves obscured by the predominant vertical interaction-logic (see for instance the contributions in part VII of Bauer and Trondal 2015).

A second gap in research is the lack of inclusion of a spatial dimension into the EAS: while the temporal and functional stipulation of the EAS has been recognized (Howlett and Goetz 2014), it’s very relevant spatial dimension is still less well reflected in the literature. The astonishing “spacelessness” of the EAS in most academic writing somewhat contradicts to well established concepts and traditions of public administration (König 2008; Schimanke 2010). Territorial cooperation, as I will try to demonstrate below, can add such a spatial connotation to conceptual reflections about the EAS, thus laying the ground for a differentiated understanding of what the notion of EAS can mean in practical terms (both with regard to the design and the implementation of European policies). Drawing on neo-institutionalist concepts, the concept of “territorial institutionalism”, which I describe below, can stimulate new research interests in this respect.

A third observation is that most of the literature on the EAS focuses on officially established (and legally based) administrative arrangements and institutions, e.g. the Commission, Parliament, Council, agencies, expert groups etc. and their formal and/or informal interlinks with other institutional equivalents at different levels. Less analyzed, however, are the patterns of vertical and horizontal administrative interaction within so-called “unsettled administrative spaces” (Trondal and Peters 2015). There are numerous examples of these, such as networks, forums, projects, committees, programs etc., which go beyond classical, functionally “closed” European organizational arrangements. Such unsettled administrative spaces can attract the attention of researchers to new and yet less analyzed interactions between European administrative actors and their thematic or sectorial administrative environments. The example of a nascent European territorial governance-system, which in itself is inter-sectorial per-se, can also illustrate to what extent the study of such unsettled patterns might contribute to a more holistic understanding of the EAS.

Ultimately drawing on European Territorial cooperation (ETC), this article assesses three key analytical questions: 1. to what extent can patterns of ETC-related institutionalization be interpreted as part of a horizontal dimension of the EAS?, 2. how can these patterns be conceptualized and what explains the diversity of this kind of institutionalization?, 3. in which regard is the reflection on the horizontal dimension of EAS productive for further research in this field?

The article first assesses the governance model of European territorial cooperation as a mode of “unsettled” horizontal transnational policy-making (section 2). Based on recent empirical evidence from the field of cross-border cooperation and applying the three criteria of Trondal/Peter’s concept of EAS II, section 3 then analyzes to what extent the administrative foundations of territorial cooperation can be understood as a horizontal dimension of the EAS. Section 4 assesses how the identified institutional patterns can be classified and explained. It develops a broader theoretical conceptualization of these findings from the perspective of neo-institutionalist assumptions, laying the ground for further prospective research on the territorial dimension(s) of the EAS from a transnational perspective.

2. European Territorial Cooperation – A Pattern of Unsettled Horizontal Administrative Governace

Territoriality is a key construction principle of Public Administration. In a classical understanding, administrative territoriality is linked to the notion of the nation state, characterized by internal and external sovereignty over its territory (König 2008, 27). Accordingly, administrative borders, which are mostly designed according to spatial criteria such as reachability, efficiency in terms of organizational redundancy-avoidance or effectiveness in terms of service delivery, usually not only determine the external limit of competence of a given administrative unit, but also define the internal relations and interfaces between different administrative levels and/or units that do exist within a state.

In the context of territorial development, the interlinkage between the processes of territorialization and institutional change is currently discussed under the theoretical assumption of regional governance (Kilper 2010). It is assumed, that in the context of territorial development a huge variety of different forms of institutionalism can be observed, ranging from rather informal networks, over sectorial projects to classical inter-local cooperations or newly set up and/or changed regional government organizations (Kleinfeld, Plamper, and Huber 2006). The shaping of a territorial governance mode, and thus the specific form of institutionalism it represents as corridor of (and for) collective action, is the result of processes, which interlink different actors, levels, sectors and decision modes on the basis of given territorial development needs (Fürst 2011). Different to approaches, developed within the national/domestic context of a uniform jurisdiction, regional governance and it’s related processes of institutional capacity-building of cross-border territories takes place between the diverging politico-administrative, legal and cultural systems of different jurisdictions. In order to support such forms of cooperation, which is often hindered by a high level of obstacles, the European Commission has promoted cross-border cooperation under a policy-approach, which is now known as “European Territorial Cooperation” (ETC).

Territorial cooperation has become increasingly important in Europe over the last 25 years. Two main factors have influenced the emergence of this policy-field. One the one hand, with the fall of the iron curtain, more than 27,000 km of new borders have emerged in Central and Eastern Europe (Foucher 2007) and the question of how to manage transnational relations at a decentralized, territorial level has become a very practical challenge for many new border regions. Secondly longtime experience from “older” border regions in Western Europe, that initiated territorial cooperation-approaches right after World War II (Wassenberg 2007), has demonstrated both the need for and the potentials of territorial cooperation for the process of European integration (AGEG 2008): NUTS 2-level statistics1 show that nearly 40% of EU territory can be classified as being a border-region with 30% of the EU population living there (MOT 2007; AGEG 2008). With the official inclusion of the territorial cohesion objective in the Lisbon treaty, the case of territorial cooperation has been strengthened within the European cohesion policy (Ahner and Fuechtner 2010; Bailo and Menier 2012), even promoting a perception of border-regions as laboratories for European integration (Kramsch and Hooper 2004; Lambertz 2010).

With regard to territorial institutionalism, the policy-approach of European territorial cooperation (ETC), can be separated into two interlinked basic patterns: the first and most obvious patterns are the INTERREG-funding programs of the European Commission which – after an experimental phase between 1988 and 1989 – were both conceptually (starting as a community initiative under INTRRREG I and II, being integrated into the structural funds regulation under INTERREG II and IV and leading to an own regulation under INTRREG V) and financially (increasing from initially 1.1 billion Euro up to 10.1 billion Euro, with nearly 7 billion Euro exclusively dedicated to cross-border cooperation) expanded over five phases with a programmatic differentiation of three strands (A = Cross-border cooperation with a focus on proximity-relations at contiguity-level; B = Transnational cooperation with a focus on planning in strategic areas relevant for European cohesion; C: Interregional cooperation with a focus on networking and exchange of good practices).2 Although transnational territorial institution-building is not the main focus of this approach, it has – as I will show in the next chapter – contributed significantly to the creation of cross-border institutional capacities both at the level of projects and program-related governance structures.

The second pattern goes beyond INTERREG-financed programs and projects and focuses directly on transnational/cross-border institution-building at a territorial level (Beck 2017). The most well-known examples here are the so-called Euregios which were built-up between Germany and its western neighbors already from the 1950s onwards, Inter-governmental Commissions with territorial differentiations such as the Upper-Rhine Conference, the Øresund Council / Greater Copenhagen and Skåne Committee, Grand-Region Summit (formerly known as SaarLorLux) which were created from the 1970s to 1990s onwards or the more recent EURODISTRICTS. Here, territorial actors are developing approaches of political and administrative cooperation either to solve specific problems, to develop territorial potentials jointly or to implement European sectoral policies in a coordinated way with the aim of fostering integrated territorial development on a border-crossing basis. As these bodies usually are not equipped with a specific budget, their functioning often depends on EU-funding. With the creation of a specific legal form, the EGTC (European Grouping of Territorial Cooperation), however, the European Commission in 2006 also tried to strengthen this form of territorial cooperation.3

The governance mode of territorial cooperation varies according to these two basic approaches. The so-called “INTERREG-world” is characterized by a pattern in which both the financial and thematic design is negotiated vertically between Member States and the EU-level, leading to a specific form of result-oriented framework planning, where core elements such as strategic objectives, specifications regarding financial management and control or basic cooperation principles (such as partnership, co- and pre-financing etc.) are defined by the Commission, but are then horizontally embellished at a decentral level by the very territorial actors themselves (design of a territorial development strategy, details of the rules, generation and selection of projects, co-financing etc.). Regarding the second pattern of territorial cooperation, the distinguishing feature here is the absence of any European or national programing: cooperation approaches between public (and private) actors from either side of the border are developed bottom-up on a purely voluntary basis. No legal or financial program is determining or actively demanding cross-border-cooperation involvement at this level and competencies, roles, procedures and forms must be negotiated and designed horizontally on the basis of voluntary decisions.

Following René Frey (2003), territorial cooperation can be perceived as a horizontal sub-system created and run by the domestic partners participating, in order to create a tangible inter-institutional network allowing for the joint design and implementation of both institutional arrangements, programs and projects (Beck 2013). As the practical functioning of this sub-system is not ensured per se but must rather be stabilized by and thus (often even on an ad hoc basis) depends on the contributions of the domestic partners involved, this leads to an unsettled, rather than formally established governance mode. Both INTERREG, which indeed is formally established and structured by decentral conventions, and institutional cooperation, which often is based on bi-lateral agreements and conventions too, are de facto fragile creations, which can erode very easily, once the necessary financial, logistical, administrative or political support provided by the partners involved is no longer forthcoming (Kramsch andHooper 2004).

ETC can be interpreted as a specific form of administrative capacity building which is based on transnational territoriality with a specific relevance of direct horizontal administrative interaction between subnational and local actors in order to handle challenges of territorial development and cohesion. Different to the domestic context, where this takes place within a uniform jurisdiction and where a European connotation is not given per se, the territorial dimension of this transnational administrative capacity-building is directly linked with the process of European integration. It’s unsettled character also distinguishes territorial cooperation from vertical, multi-level administrative interaction, taking place within the settled constellations of the classical European administrative system (Bauer and Trondal 2015). As I will demonstrate in the next chapter, territorial cooperation has over time generated a marked permanent horizontal administrative profile, worthy to study in the context of the EAS.4

3. The Administrative Dimension of European Territorial Cooperation (ETC)

In order to analyze the administrative dimension of territorial cooperation and its possible relation/contribution to the EAS in more detail, my analytical approach refers to the concept of EAS II developed by Trondal and Peters (2015). Accordingly, an EAS is existent only if three main characteristics are met: (1) An EAS needs to represent an independent institutional capacity for handling European Affairs differently. (2) An EAS needs to be characterized by a structure of integrated administrative action, allowing for the effective coordination of administrative units to fulfill European tasks; (3) The EAS is characterized by co-optation in the sense that it constitutes a recognized partner for external actors and utilizes their potentials for its own tasks and/or a joint task-delivery.

3.1. Independence of Institutional Capacity

Different indicators for analyzing the institutional capacity of territorial cooperation in Europe are possible. As the independence of institutional capacity is a central criterion of the EAS, I will concentrate my analysis on two main indicators Firstly I will identify the overall numbers of transnational institutional arrangements at different functional levels. The relevance of this indicator refers to the path-dependency hypothesis of neo-institutionalism (Pierson 2004) and assesses the distinction between the given institutional capacity-path of the national partners involved and the specificly created transnational/cross-border capacity path.

The second indicator refers to ETC-related personnel-capacity, measured in the form of FTE (full time equivalence). This indicator is relevant for the identification of an independent institutional capacity in the sense that FTE’s exclusively established for and working on ETC-related issues are representing an independent transnational/cross-border capacity.5

In order to apply both indicators my first analytical approach is to determine the overall number of ECT programs officially co-financed by the European Union. According to the official statistics6 the number of INTERREG-programs (all strands) has evolved considerably over the last 25 years. Starting with only 14 pilot-projects in 1988, the first INTERREG period (1990–1993) saw the creation of 31, the second (1994–1999) 59, the third (2000–2006) 79, the fourth (2007–2013) 92 and the current (2014–2020) of over 107 ECT programs, with 60 exclusively focusing on cross-border cooperation. Under strand A alone, 14,965 projects have been funded and for the most part already implemented during the last INTERREG IV period, leading to the creation of 50,179 new cross-border partnerships between mostly public actors. Given the three-year-average duration of the projects, a permanent annual project-capacity of 6,413 and a permanent partnership capacity of 21,505 was created over the seven years of this programing period.

In terms of administrative capacity it is worth remembering, that, according to the EU-regulations, each ETC program has to create a specific management structure at a decentral horizontal level. This management structure is composed of a Monitoring/Steering committee, responsible for determining the program strategy and the selection of projects (usually composed of the program partners at MS-level and/or their nominated sub-national representatives), a managing authority, responsible for the operational management and implementation of the program (technical representatives of the program partners) a joint secretariat, responsible for the day to day implementation of the program, the project generation and the preparation of documents and reports for the meetings of the other structures (program officials financed by the overhead of the respective program).7 In addition, the programs and projects are also creating respective transnational institutionalizations in the form of legal conventions or agreements, committing public partners with regard to financial obligations, thematic contributions and procedural patterns such as roles during the implementation and/or modes of decision-making etc. INTERREG IV has led to the conclusion of more than 15,000 of such conventions interconnecting public actors both at Member State, sub-national, regional and local levels – either for the duration of the entire programing period or at least for the funding period of an individual project – thus structuring the model of transnational action in many cross-border territories of Europe.

While both the steering committee and the managing authority-functions are in practice quite often carried out by administrative representatives of the program partners on a part-time basis, the members of the joint secretariats are usually employed on a full-time basis – either in the form of seconded national experts or directly recruited and employed by the program. It is difficult to quantify the number of officials working in the ETC-programs as the practical implementation of the management structures varies between programs. However, a realistic estimate of the number of officials working at program-level can be calculated on the basis of the share of personnel costs as part of the overall budget dedicated to technical assistance (which de facto covers the overall overhead costs of a program). In the absence of valid statistical information, it can be estimated that the average number of officials working at the level of the Management Authority and the Joint secretariat amounts to 10 FTE,8 which would mean that under the current funding period of INTERREG V a capacity of 1,070 FTEs exists for the management of the ETC programs in Europe. In addition, most INTERREG-projects require professional handling of both the formal and the thematic implementation and thus usually lead to the development of professional capacity for project-management, eligible for INTERREG-funding. Under the assumption that the project-management capacity per INTERREG project amounts to at least 2 FTE/project,9 INTERREG IV has – between 2007 and 2013 – created a permanent project-based capacity of 12,826 FTE’s.

My second analytical perspective goes beyond the very approach of EU-funded ETC. In addition to the “INTERREG-world”, many other forms of horizontal administrative cooperation, taking place at different transnational territorial levels, have evolved in Europe over time. In a recent study, Reitel and Wassenberg (2015, 19) have developed a classification that distinguishes at the local scale between the urban spatial dimension (cooperation between two or more contiguous urban municipalities like Frankfurt/Oder – Slubice; Eurode Kerkrade-Herzogenrath) and the rural spatial dimension (cooperation between contiguous municipal/intermunicipal bodies in sparsely built-up areas like Pyrenees-Cerdanya or the Mont Blanc Area); at the regional scale between the cross-border metropolitan spatial dimension (cooperation between contiguous territories – NUTS 3 or 4 – with a monocentric or polycentric metropolitan structure like the Basel Trinational Eurodistrict, the Meuse-Rhine Eurodistrict or the Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai Eurometropolis) and the non-metropolitan dimension (cooperation between contiguous territories – NUTS 3 or 4 – without a metropolitan structure like the Euregios or the Catalan cross-border Area Eurodistrict); and at the supraregional scale between the metropolitan dimension (cooperation between contiguous territories -NUTS 2 or 3- with a metropolitan degree like The Greater Region or the Upper-Rhine) and the non-metropolitan dimension like the Channel Arc. According to this typology, Reitel and Wassenberg (2015) identified 364 “recognized frameworks” (18) of institutional cross-border cooperation in the EU. To this can be added a macro-regional scale with cooperation approaches integrating classical cross-border, inter-regional and transnational levels into a broader territorial space covering more than 3 member states on the basis of shared territorial characteristics (such as the Baltic Sea; the Danube region, the Adriatic/Ionian Sea, or the Alps).

From the point of territorial institutional capacity-building, the most relevant forms of such kinds of inter-administrative cooperation “beyond INTERREG” are inter-local/euro-regional (local and regional level) and inter-governmental/network (supra- and macro-regional level) approaches. The Association of European Border regions (AEBR) has identified a total of nearly 200 euro-regional cooperations in Europe, the great majority of them running permanent secretariats with full-time staff. Under the assumption that at least 80% of these Euroregions have a permanent joint secretariat with a minimum average of 3 FTE’s (not carrying out INTERREG-management functions, but project- and other management tasks related to the euro-regional working structures), the horizontal “euro-regional” institutional capacity created here would be around 480 FTE’s. In addition, most of these Euro-regional cooperation structures are law-based, aiming at a more binding and sustainable transnational administrative interconnection than a simple project convention. In addition, more than 50 European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC), have been created so far in Europe, mostly not used, however, to structure euro-regional tasks but rather fulfilling project-based cooperation and implementation needs for the participating partners (European Parliament 2015).

Less well documented are inter-governmental bodies and commissions which have been set up between many Member states from the 1970s onwards. Based on bilateral agreements such intergovernmental structures and bodies are very often determining the cross-border cooperation of an entire border-zone between two or more states, with a historically strong participation of officials coming from either national ministries or administrative units of the sub-national state-level (like ministries of the governments of the German Länder, the préfecture in France, the woiwode-province in Poland etc.). Most of these inter-governmental bodies are differentiated organizationally into territorial and/or thematic sub-units. The horizontal administrative capacities created and symbolized by these intergovernmental bodies are varying greatly between these cross-border territorial constellations. While, for example, around 600 representatives from the respective subnational and regional governments of Baden-Württemberg, Rheinland-Pfalz, Alsace and Northwestern Switzerland are collaborating in 12 standing thematic working-groups on a regular part-time basis in the Trilateral Conference of the Upper-Rhine, the 6 Agreement-implementing North/South bodies on the Irish/UK border involve 578 FTE’s overall in 2013.

In addition, with the recent initiatives to create European macro-regions, specific transnational governance-structures have emerged, interlinking the three levels of meta-governance (interaction between the European Commission, the European Council, a high-level group, national contact points and annual forums), thematic governance (Priority area coordinators, steering groups, governing boards, thematic working groups) and implementation-governance (project partners and the respective financing programs and institutions) (Sielker 2014, 89). The hundreds of new project initiatives, plus the annual forums with more than thousand participants each, represent a complex mix of public and private and/or third sector actors, yet still inter-administrative cooperation is at the core of the macro-regional approach.

In order to capture the full picture, however, a more valid approach to providing an estimate is needed. One established method to calculate the personnel-needs for an administrative unit – in the absence of quantitative figures – is to develop a realistic vision of the administrative overhead (FTE) required per million inhabitants (Hopp and Göbel 2008, 329). Applying this method to the context of territorial cooperation, a pilot survey carried out by the author among members of the TEIN-Network,10 came to the conclusion, that – in the case of cross-border cooperation – an average administrative overhead relation of 55 FTE per million inhabitants of a cross-border territory can be realistically assumed.11 This indicator can be used for an extrapolation of the administrative CBC capacity at the level of the entire European territory: based on the assumption that at NUTS 2-level 150 million EU inhabitants (e.g. 30% of the EU population) are living in border-regions,12 one can estimate a total direct horizontal administrative capacity of 8,250 FTE. Adding the above calculated permanent capacity generated at project level (12,826 FTE), the total number of independent horizontal cross-border capacity would thus amount to 21,076 FTE’s. The overall horizontal capacity of the entire European territorial cooperation, however, would certainly be significantly higher, as this figure is only a conservative estimate for the narrower range of cross-border cooperation at contiguity level, leaving aside the many other forms and levels of transnational co-operations taking place with or without EU funding in this regard. Compared to the administrative capacity of Member states, and especially with regard of the 10,765,424 public employees working in Europe’s border-regions without being involved in ETC,13 however, this remains still a rather weak profile. The analysis of both indicators is suggesting a somehow paradoxical conclusion: On the one hand, they are indicating the existence of an independent institutional capacity for handling ETC affairs differently on a horizontal basis. Yet the overall contextualization of this finding indicates a relatively week profile of the transnational/cross-border compared to the domestic institutional path. I will take up this finding in the next chapter, where I will interpret this horizontal ETC-profile from the point of neo- institutional theory.

3.2. Integration

Regarding the second criterion of the EAS, which refers to the existence of a distinct administrative and functional integration, the case of territorial cooperation is interesting too. The main pattern of territorial cooperation is still the project-approach. For a long time, the Leitmotiv in the trans-national/cross-border context was ultimately, the project would create the territory and not the other way around (Casteigts 2010, 305). Project development, however, has changed considerably over the years. While in the early times of INTERREG I and II most territorial cooperation was characterized by a strong bottom-up approach, leading to a patchwork of relatively isolated individual projects and related networks, project generation has now become more and more strategic in the sense, that project selection is more often based on calls of proposals, which themselves serve the implementation of strategic development objectives jointly agreed upon by the program partners (Marin 1990). A typical example is the thematic concentration principle demanded by the EU-Commission under INTERREG V, which most territorial programs managed to respect and which signifies the attempt for a much more integrated policy-coordination, leading to new forms of integrated horizontal administrative cooperation between local and regional partners. Beyond INTERREG, many Euregios and Eurodistricts, but also territorial cooperation approaches at a supra-regional level, like the Upper-Rhine, the Great Region, the Lake of Constance, the Oeresund, not to speak of the European macro-regions, have developed integrated development strategies and increasingly use strategic objectives as selection criteria for the identification of “lighthouse” projects with positive spillovers for the entire transnational territory.

The second pattern relevant in this regard concerns the role of political leadership. Territorial cooperation is usually supported by political networks of high-level decision-makers who actively request it (Hansen and Serin 2010, 207). Party-political preferences, however, are much less important than in the domestic context. The administrative officials responsible for territorial cooperation at the level of the participating partner institutions are mostly located very close to the top political leadership of these institutions (cabinets, government offices both at local, regional and sub-national level). This gives such officials “borrowed” power, allowing for a relatively strong position both in relation to the classical thematic organizational divisions of their domestic administrations and in relation to their counterparts from the neighboring state. Close and functional inter-personal network constellations (Jansen and Schubert 1995; Marin and Mayntz 1990) are created in this way, which in turn lead to functional patterns of informal preliminary decision-making at a technical level thus developing relatively stable modes of interlinked transnational executive leadership and government (Beck et al. 2015).

A third, closely linked, pattern, is that productive territorial cooperation approaches at a transnational/cross-border scale can manage to develop inter-personal networks of trust enabling the surmounting of formal administrative differences (Chrisholm 1989). This may lead to a pattern of ever growing synchronization of domestic capacities for transnational purposes, based on inter-institutional decision-making at an informal level. In most transnational territorial policy-making today there is a high level of synchronization and horizontal coordination plus an increasing attempt to develop more integrated approaches. Whereas in the past, mainly distributive policies were dealt with at the transnational level, today successful transnational territorial cooperation can even allow for redistributive decisions (like joint approaches to a more integrated labor-market policy, economic and tourist development (Zschiedrich 2011) or transport-policy (Drewello and Scholl 2015), thereby trying to overcome classical territorial “location-egos” of the partners in favor of promoting the development needs of the entire territory.

Ultimately, a fourth pattern should be mentioned: in contrast to the ordinary population, which still has a rather domestic territorial reference frame (Schönwald 2010), actors of trans-national territorial cooperation have a particularly strong identification with CBC issues. A recent survey amongst 132 cross-border actors, applying the analytical variables of the international GLOBE-project (Chhokar, Brodbeck, and House 2007) at the transnational territorial level (Beck et al. 2015), identified a strongly mission driven cooperation culture, based on shared belief-systems, which results in the transnational subsystem of cooperation de facto being a close community of committed actors, distinguishing itself clearly from the institutional domestic context with regards to variables, such as in-group and institutional-collectivism, power-distance, human-orientation, assertiveness or uncertainty avoidance. This mirrors, however, that on the other hand CBC affaires are obviously still mostly an issue for politico-administrative elites (Decoville and Durand 2018).

The second indicator refers to ETC-related personnel-capacity, measured in the form of FTE (full time equivalence). This indicator is relevant for the identification of an independent institutional capacity in the sense that FTE’s exclusively established for and working on ETC-related issues are representing an independent transnational/cross-border capacity.5

In order to apply both indicators my first analytical approach is to determine the overall number of ECT programs officially co-financed by the European Union. According to the official statistics6 the number of INTERREG-programs (all strands) has evolved considerably over the last 25 years. Starting with only 14 pilot-projects in 1988, the first INTERREG period (1990–1993) saw the creation of 31, the second (1994–1999) 59, the third (2000–2006) 79, the fourth (2007–2013) 92 and the current (2014–2020) of over 107 ECT programs, with 60 exclusively focusing on cross-border cooperation. Under strand A alone, 14,965 projects have been funded and for the most part already implemented during the last INTERREG IV period, leading to the creation of 50,179 new cross-border partnerships between mostly public actors. Given the three-year-average duration of the projects, a permanent annual project-capacity of 6,413 and a permanent partnership capacity of 21,505 was created over the seven years of this programing period.

In terms of administrative capacity it is worth remembering, that, according to the EU-regulations, each ETC program has to create a specific management structure at a decentral horizontal level. This management structure is composed of a Monitoring/Steering committee, responsible for determining the program strategy and the selection of projects (usually composed of the program partners at MS-level and/or their nominated sub-national representatives), a managing authority, responsible for the operational management and implementation of the program (technical representatives of the program partners) a joint secretariat, responsible for the day to day implementation of the program, the project generation and the preparation of documents and reports for the meetings of the other structures (program officials financed by the overhead of the respective program).7 In addition, the programs and projects are also creating respective transnational institutionalizations in the form of legal conventions or agreements, committing public partners with regard to financial obligations, thematic contributions and procedural patterns such as roles during the implementation and/or modes of decision-making etc. INTERREG IV has led to the conclusion of more than 15,000 of such conventions interconnecting public actors both at Member State, sub-national, regional and local levels – either for the duration of the entire programing period or at least for the funding period of an individual project – thus structuring the model of transnational action in many cross-border territories of Europe.

While both the steering committee and the managing authority-functions are in practice quite often carried out by administrative representatives of the program partners on a part-time basis, the members of the joint secretariats are usually employed on a full-time basis – either in the form of seconded national experts or directly recruited and employed by the program. It is difficult to quantify the number of officials working in the ETC-programs as the practical implementation of the management structures varies between programs. However, a realistic estimate of the number of officials working at program-level can be calculated on the basis of the share of personnel costs as part of the overall budget dedicated to technical assistance (which de facto covers the overall overhead costs of a program). In the absence of valid statistical information, it can be estimated that the average number of officials working at the level of the Management Authority and the Joint secretariat amounts to 10 FTE,8 which would mean that under the current funding period of INTERREG V a capacity of 1,070 FTEs exists for the management of the ETC programs in Europe. In addition, most INTERREG-projects require professional handling of both the formal and the thematic implementation and thus usually lead to the development of professional capacity for project-management, eligible for INTERREG-funding. Under the assumption that the project-management capacity per INTERREG project amounts to at least 2 FTE/project,9 INTERREG IV has – between 2007 and 2013 – created a permanent project-based capacity of 12,826 FTE’s.

My second analytical perspective goes beyond the very approach of EU-funded ETC. In addition to the “INTERREG-world”, many other forms of horizontal administrative cooperation, taking place at different transnational territorial levels, have evolved in Europe over time. In a recent study, Reitel and Wassenberg (2015, 19) have developed a classification that distinguishes at the local scale between the urban spatial dimension (cooperation between two or more contiguous urban municipalities like Frankfurt/Oder – Slubice; Eurode Kerkrade-Herzogenrath) and the rural spatial dimension (cooperation between contiguous municipal/intermunicipal bodies in sparsely built-up areas like Pyrenees-Cerdanya or the Mont Blanc Area); at the regional scale between the cross-border metropolitan spatial dimension (cooperation between contiguous territories – NUTS 3 or 4 – with a monocentric or polycentric metropolitan structure like the Basel Trinational Eurodistrict, the Meuse-Rhine Eurodistrict or the Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai Eurometropolis) and the non-metropolitan dimension (cooperation between contiguous territories – NUTS 3 or 4 – without a metropolitan structure like the Euregios or the Catalan cross-border Area Eurodistrict); and at the supraregional scale between the metropolitan dimension (cooperation between contiguous territories -NUTS 2 or 3- with a metropolitan degree like The Greater Region or the Upper-Rhine) and the non-metropolitan dimension like the Channel Arc. According to this typology, Reitel and Wassenberg (2015) identified 364 “recognized frameworks” (18) of institutional cross-border cooperation in the EU. To this can be added a macro-regional scale with cooperation approaches integrating classical cross-border, inter-regional and transnational levels into a broader territorial space covering more than 3 member states on the basis of shared territorial characteristics (such as the Baltic Sea; the Danube region, the Adriatic/Ionian Sea, or the Alps).

From the point of territorial institutional capacity-building, the most relevant forms of such kinds of inter-administrative cooperation “beyond INTERREG” are inter-local/euro-regional (local and regional level) and inter-governmental/network (supra- and macro-regional level) approaches. The Association of European Border regions (AEBR) has identified a total of nearly 200 euro-regional cooperations in Europe, the great majority of them running permanent secretariats with full-time staff. Under the assumption that at least 80% of these Euroregions have a permanent joint secretariat with a minimum average of 3 FTE’s (not carrying out INTERREG-management functions, but project- and other management tasks related to the euro-regional working structures), the horizontal “euro-regional” institutional capacity created here would be around 480 FTE’s. In addition, most of these Euro-regional cooperation structures are law-based, aiming at a more binding and sustainable transnational administrative interconnection than a simple project convention. In addition, more than 50 European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC), have been created so far in Europe, mostly not used, however, to structure euro-regional tasks but rather fulfilling project-based cooperation and implementation needs for the participating partners (European Parliament 2015).

Less well documented are inter-governmental bodies and commissions which have been set up between many Member states from the 1970s onwards. Based on bilateral agreements such intergovernmental structures and bodies are very often determining the cross-border cooperation of an entire border-zone between two or more states, with a historically strong participation of officials coming from either national ministries or administrative units of the sub-national state-level (like ministries of the governments of the German Länder, the préfecture in France, the woiwode-province in Poland etc.). Most of these inter-governmental bodies are differentiated organizationally into territorial and/or thematic sub-units. The horizontal administrative capacities created and symbolized by these intergovernmental bodies are varying greatly between these cross-border territorial constellations. While, for example, around 600 representatives from the respective subnational and regional governments of Baden-Württemberg, Rheinland-Pfalz, Alsace and Northwestern Switzerland are collaborating in 12 standing thematic working-groups on a regular part-time basis in the Trilateral Conference of the Upper-Rhine, the 6 Agreement-implementing North/South bodies on the Irish/UK border involve 578 FTE’s overall in 2013.

In addition, with the recent initiatives to create European macro-regions, specific transnational governance-structures have emerged, interlinking the three levels of meta-governance (interaction between the European Commission, the European Council, a high-level group, national contact points and annual forums), thematic governance (Priority area coordinators, steering groups, governing boards, thematic working groups) and implementation-governance (project partners and the respective financing programs and institutions) (Sielker 2014, 89). The hundreds of new project initiatives, plus the annual forums with more than thousand participants each, represent a complex mix of public and private and/or third sector actors, yet still inter-administrative cooperation is at the core of the macro-regional approach.

In order to capture the full picture, however, a more valid approach to providing an estimate is needed. One established method to calculate the personnel-needs for an administrative unit – in the absence of quantitative figures – is to develop a realistic vision of the administrative overhead (FTE) required per million inhabitants (Hopp and Göbel 2008, 329). Applying this method to the context of territorial cooperation, a pilot survey carried out by the author among members of the TEIN-Network,10 came to the conclusion, that – in the case of cross-border cooperation – an average administrative overhead relation of 55 FTE per million inhabitants of a cross-border territory can be realistically assumed.11 This indicator can be used for an extrapolation of the administrative CBC capacity at the level of the entire European territory: based on the assumption that at NUTS 2-level 150 million EU inhabitants (e.g. 30% of the EU population) are living in border-regions,12 one can estimate a total direct horizontal administrative capacity of 8,250 FTE. Adding the above calculated permanent capacity generated at project level (12,826 FTE), the total number of independent horizontal cross-border capacity would thus amount to 21,076 FTE’s. The overall horizontal capacity of the entire European territorial cooperation, however, would certainly be significantly higher, as this figure is only a conservative estimate for the narrower range of cross-border cooperation at contiguity level, leaving aside the many other forms and levels of transnational co-operations taking place with or without EU funding in this regard. Compared to the administrative capacity of Member states, and especially with regard of the 10,765,424 public employees working in Europe’s border-regions without being involved in ETC,13 however, this remains still a rather weak profile. The analysis of both indicators is suggesting a somehow paradoxical conclusion: On the one hand, they are indicating the existence of an independent institutional capacity for handling ETC affairs differently on a horizontal basis. Yet the overall contextualization of this finding indicates a relatively week profile of the transnational/cross-border compared to the domestic institutional path. I will take up this finding in the next chapter, where I will interpret this horizontal ETC-profile from the point of neo- institutional theory.

3.3. Co-optation

Because the sub-systems of territorial cooperation are mostly not yet equipped with proper competencies and / or a sound legal basis by their constituent politico-administrative environments, co-optation can be understood as a sine qua non-condition for their proper functioning. Territorial cooperation is a permanent bargaining process both between the very actors coming from different systemic and cultural administrative backgrounds and between actors on the spot, having to persuade their institutional, political and legal superiors when more substantive engagements beyond symbols are required. Co-optation in this regards means both forging coalitions for “win/win” constellations and gaining the necessary institutional and financial support from the domestic partners and the national governments (Beck and Wassenberg 2011).

A second field, where co-optation takes place, is the strategic approach for gaining support from the European level. It is interesting to see, how, after long years of decoupling, relevant co-optation approaches from cross-border territories have become more and more successful in this regard: starting from the pilot-phase of 1989, when cross-border issues were included in the general approach of the European cohesion policy for the first time, followed by the establishment of INTERREG as Community Initiative and then it’s coming into being as a mainstream program, the creation of the EGCT-regulation, the approach of macro-regions, the green paper on territorial cohesion, today the big efforts by the Commission to address the structural obstacles to cross-border cooperation or the proposal of the CoR to develop a specific Territorial Impact Assessment for border-regions14 – all these developments can be interpreted as the result of cross-border actors, trying to gain support from the European Institutions in order to increase the pressure on national and sub-national governments to better support initiatives coming from the bottom of the cross-border territories (Keating 1998; Harguindéguy and Sànchez-Sánchez 2017).

A third level of co-optation consists of more recent attempts at developing inter-sectoral territorial governance approaches. Whereas cross-border cooperation has been the quasi exclusive domain of administrative actors in the last 40 years, more recently new forms of territorial governance increasingly are being developed in the cross-border context. These are inspired by good practices taking place within the domestic context of regional governance (Fürst 2011) and are characterized by integrated networks of actors coming from the economic, the societal, the research and the public sector, combined with new participative approaches and forms of collective policy-development (Kilper 2010). For the existing sub-system of cross-border cooperation such newly designed approaches present opportunities to co-opt existing capacities of other sectors and utilize them for the purpose of transnational territorial institution-building: newly created boards and platforms, specific INTERREG-projects, steering committees, governing-bodies with (or without) a permanent secretariat-function etc. contribute to the horizontal networking of new economic, societal, scientific actors, thus both increasing the sector-specific and the inter-sectoral capacity building at the horizontal level, leading to new dynamics and growth-paths for cross-border policy making which in turn ultimately strengthens the administrative actors involved at the spot (Jansen and Schubert 1995).

The second pattern relevant in this regard concerns the role of political leadership. Territorial cooperation is usually supported by political networks of high-level decision-makers who actively request it (Hansen and Serin 2010, 207). Party-political preferences, however, are much less important than in the domestic context. The administrative officials responsible for territorial cooperation at the level of the participating partner institutions are mostly located very close to the top political leadership of these institutions (cabinets, government offices both at local, regional and sub-national level). This gives such officials “borrowed” power, allowing for a relatively strong position both in relation to the classical thematic organizational divisions of their domestic administrations and in relation to their counterparts from the neighboring state. Close and functional inter-personal network constellations (Jansen and Schubert 1995; Marin and Mayntz 1990) are created in this way, which in turn lead to functional patterns of informal preliminary decision-making at a technical level thus developing relatively stable modes of interlinked transnational executive leadership and government (Beck et al. 2015).

A third, closely linked, pattern, is that productive territorial cooperation approaches at a transnational/cross-border scale can manage to develop inter-personal networks of trust enabling the surmounting of formal administrative differences (Chrisholm 1989). This may lead to a pattern of ever growing synchronization of domestic capacities for transnational purposes, based on inter-institutional decision-making at an informal level. In most transnational territorial policy-making today there is a high level of synchronization and horizontal coordination plus an increasing attempt to develop more integrated approaches. Whereas in the past, mainly distributive policies were dealt with at the transnational level, today successful transnational territorial cooperation can even allow for redistributive decisions (like joint approaches to a more integrated labor-market policy, economic and tourist development (Zschiedrich 2011) or transport-policy (Drewello and Scholl 2015), thereby trying to overcome classical territorial “location-egos” of the partners in favor of promoting the development needs of the entire territory.

Ultimately, a fourth pattern should be mentioned: in contrast to the ordinary population, which still has a rather domestic territorial reference frame (Schönwald 2010), actors of trans-national territorial cooperation have a particularly strong identification with CBC issues. A recent survey amongst 132 cross-border actors, applying the analytical variables of the international GLOBE-project (Chhokar, Brodbeck, and House 2007) at the transnational territorial level (Beck et al. 2015), identified a strongly mission driven cooperation culture, based on shared belief-systems, which results in the transnational subsystem of cooperation de facto being a close community of committed actors, distinguishing itself clearly from the institutional domestic context with regards to variables, such as in-group and institutional-collectivism, power-distance, human-orientation, assertiveness or uncertainty avoidance. This mirrors, however, that on the other hand CBC affaires are obviously still mostly an issue for politico-administrative elites (Decoville and Durand 2018).

The second indicator refers to ETC-related personnel-capacity, measured in the form of FTE (full time equivalence). This indicator is relevant for the identification of an independent institutional capacity in the sense that FTE’s exclusively established for and working on ETC-related issues are representing an independent transnational/cross-border capacity.5

In order to apply both indicators my first analytical approach is to determine the overall number of ECT programs officially co-financed by the European Union. According to the official statistics6 the number of INTERREG-programs (all strands) has evolved considerably over the last 25 years. Starting with only 14 pilot-projects in 1988, the first INTERREG period (1990–1993) saw the creation of 31, the second (1994–1999) 59, the third (2000–2006) 79, the fourth (2007–2013) 92 and the current (2014–2020) of over 107 ECT programs, with 60 exclusively focusing on cross-border cooperation. Under strand A alone, 14,965 projects have been funded and for the most part already implemented during the last INTERREG IV period, leading to the creation of 50,179 new cross-border partnerships between mostly public actors. Given the three-year-average duration of the projects, a permanent annual project-capacity of 6,413 and a permanent partnership capacity of 21,505 was created over the seven years of this programing period.

In terms of administrative capacity it is worth remembering, that, according to the EU-regulations, each ETC program has to create a specific management structure at a decentral horizontal level. This management structure is composed of a Monitoring/Steering committee, responsible for determining the program strategy and the selection of projects (usually composed of the program partners at MS-level and/or their nominated sub-national representatives), a managing authority, responsible for the operational management and implementation of the program (technical representatives of the program partners) a joint secretariat, responsible for the day to day implementation of the program, the project generation and the preparation of documents and reports for the meetings of the other structures (program officials financed by the overhead of the respective program).7 In addition, the programs and projects are also creating respective transnational institutionalizations in the form of legal conventions or agreements, committing public partners with regard to financial obligations, thematic contributions and procedural patterns such as roles during the implementation and/or modes of decision-making etc. INTERREG IV has led to the conclusion of more than 15,000 of such conventions interconnecting public actors both at Member State, sub-national, regional and local levels – either for the duration of the entire programing period or at least for the funding period of an individual project – thus structuring the model of transnational action in many cross-border territories of Europe.

While both the steering committee and the managing authority-functions are in practice quite often carried out by administrative representatives of the program partners on a part-time basis, the members of the joint secretariats are usually employed on a full-time basis – either in the form of seconded national experts or directly recruited and employed by the program. It is difficult to quantify the number of officials working in the ETC-programs as the practical implementation of the management structures varies between programs. However, a realistic estimate of the number of officials working at program-level can be calculated on the basis of the share of personnel costs as part of the overall budget dedicated to technical assistance (which de facto covers the overall overhead costs of a program). In the absence of valid statistical information, it can be estimated that the average number of officials working at the level of the Management Authority and the Joint secretariat amounts to 10 FTE,8 which would mean that under the current funding period of INTERREG V a capacity of 1,070 FTEs exists for the management of the ETC programs in Europe. In addition, most INTERREG-projects require professional handling of both the formal and the thematic implementation and thus usually lead to the development of professional capacity for project-management, eligible for INTERREG-funding. Under the assumption that the project-management capacity per INTERREG project amounts to at least 2 FTE/project,9 INTERREG IV has – between 2007 and 2013 – created a permanent project-based capacity of 12,826 FTE’s.

My second analytical perspective goes beyond the very approach of EU-funded ETC. In addition to the “INTERREG-world”, many other forms of horizontal administrative cooperation, taking place at different transnational territorial levels, have evolved in Europe over time. In a recent study, Reitel and Wassenberg (2015, 19) have developed a classification that distinguishes at the local scale between the urban spatial dimension (cooperation between two or more contiguous urban municipalities like Frankfurt/Oder – Slubice; Eurode Kerkrade-Herzogenrath) and the rural spatial dimension (cooperation between contiguous municipal/intermunicipal bodies in sparsely built-up areas like Pyrenees-Cerdanya or the Mont Blanc Area); at the regional scale between the cross-border metropolitan spatial dimension (cooperation between contiguous territories – NUTS 3 or 4 – with a monocentric or polycentric metropolitan structure like the Basel Trinational Eurodistrict, the Meuse-Rhine Eurodistrict or the Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai Eurometropolis) and the non-metropolitan dimension (cooperation between contiguous territories – NUTS 3 or 4 – without a metropolitan structure like the Euregios or the Catalan cross-border Area Eurodistrict); and at the supraregional scale between the metropolitan dimension (cooperation between contiguous territories -NUTS 2 or 3- with a metropolitan degree like The Greater Region or the Upper-Rhine) and the non-metropolitan dimension like the Channel Arc. According to this typology, Reitel and Wassenberg (2015) identified 364 “recognized frameworks” (18) of institutional cross-border cooperation in the EU. To this can be added a macro-regional scale with cooperation approaches integrating classical cross-border, inter-regional and transnational levels into a broader territorial space covering more than 3 member states on the basis of shared territorial characteristics (such as the Baltic Sea; the Danube region, the Adriatic/Ionian Sea, or the Alps).

From the point of territorial institutional capacity-building, the most relevant forms of such kinds of inter-administrative cooperation “beyond INTERREG” are inter-local/euro-regional (local and regional level) and inter-governmental/network (supra- and macro-regional level) approaches. The Association of European Border regions (AEBR) has identified a total of nearly 200 euro-regional cooperations in Europe, the great majority of them running permanent secretariats with full-time staff. Under the assumption that at least 80% of these Euroregions have a permanent joint secretariat with a minimum average of 3 FTE’s (not carrying out INTERREG-management functions, but project- and other management tasks related to the euro-regional working structures), the horizontal “euro-regional” institutional capacity created here would be around 480 FTE’s. In addition, most of these Euro-regional cooperation structures are law-based, aiming at a more binding and sustainable transnational administrative interconnection than a simple project convention. In addition, more than 50 European Groupings of Territorial Cooperation (EGTC), have been created so far in Europe, mostly not used, however, to structure euro-regional tasks but rather fulfilling project-based cooperation and implementation needs for the participating partners (European Parliament 2015).

Less well documented are inter-governmental bodies and commissions which have been set up between many Member states from the 1970s onwards. Based on bilateral agreements such intergovernmental structures and bodies are very often determining the cross-border cooperation of an entire border-zone between two or more states, with a historically strong participation of officials coming from either national ministries or administrative units of the sub-national state-level (like ministries of the governments of the German Länder, the préfecture in France, the woiwode-province in Poland etc.). Most of these inter-governmental bodies are differentiated organizationally into territorial and/or thematic sub-units. The horizontal administrative capacities created and symbolized by these intergovernmental bodies are varying greatly between these cross-border territorial constellations. While, for example, around 600 representatives from the respective subnational and regional governments of Baden-Württemberg, Rheinland-Pfalz, Alsace and Northwestern Switzerland are collaborating in 12 standing thematic working-groups on a regular part-time basis in the Trilateral Conference of the Upper-Rhine, the 6 Agreement-implementing North/South bodies on the Irish/UK border involve 578 FTE’s overall in 2013.

In addition, with the recent initiatives to create European macro-regions, specific transnational governance-structures have emerged, interlinking the three levels of meta-governance (interaction between the European Commission, the European Council, a high-level group, national contact points and annual forums), thematic governance (Priority area coordinators, steering groups, governing boards, thematic working groups) and implementation-governance (project partners and the respective financing programs and institutions) (Sielker 2014, 89). The hundreds of new project initiatives, plus the annual forums with more than thousand participants each, represent a complex mix of public and private and/or third sector actors, yet still inter-administrative cooperation is at the core of the macro-regional approach.

In order to capture the full picture, however, a more valid approach to providing an estimate is needed. One established method to calculate the personnel-needs for an administrative unit – in the absence of quantitative figures – is to develop a realistic vision of the administrative overhead (FTE) required per million inhabitants (Hopp and Göbel 2008, 329). Applying this method to the context of territorial cooperation, a pilot survey carried out by the author among members of the TEIN-Network,10 came to the conclusion, that – in the case of cross-border cooperation – an average administrative overhead relation of 55 FTE per million inhabitants of a cross-border territory can be realistically assumed.11 This indicator can be used for an extrapolation of the administrative CBC capacity at the level of the entire European territory: based on the assumption that at NUTS 2-level 150 million EU inhabitants (e.g. 30% of the EU population) are living in border-regions,12 one can estimate a total direct horizontal administrative capacity of 8,250 FTE. Adding the above calculated permanent capacity generated at project level (12,826 FTE), the total number of independent horizontal cross-border capacity would thus amount to 21,076 FTE’s. The overall horizontal capacity of the entire European territorial cooperation, however, would certainly be significantly higher, as this figure is only a conservative estimate for the narrower range of cross-border cooperation at contiguity level, leaving aside the many other forms and levels of transnational co-operations taking place with or without EU funding in this regard. Compared to the administrative capacity of Member states, and especially with regard of the 10,765,424 public employees working in Europe’s border-regions without being involved in ETC,13 however, this remains still a rather weak profile. The analysis of both indicators is suggesting a somehow paradoxical conclusion: On the one hand, they are indicating the existence of an independent institutional capacity for handling ETC affairs differently on a horizontal basis. Yet the overall contextualization of this finding indicates a relatively week profile of the transnational/cross-border compared to the domestic institutional path. I will take up this finding in the next chapter, where I will interpret this horizontal ETC-profile from the point of neo- institutional theory.

4. Conceptual Framing of European Territorial Institutionalism

According to the three basic criteria developed by Trondal and Peters (2015), territorial cooperation, as analyzed above, can be interpreted as a specific, horizontal pattern of the EAS. However, there are characteristics that also clearly distinguish this horizontal from the more classical vertical perspective of the EAS. First of all, the horizontal administrative profile is much less well developed both in quantitative and qualitative terms. With the challenges of an inverse principal-agent constellation, added by the lack both of substantive thematic competencies at the level of CBC bodies and the fulfillment of permanent cross-border tasks (Harguindéguy and Sànchez-Sánchez 2017, 257) the shaping of both the institutional and functional framework of territorial cooperation is still rather limited compared to the vertical dimension of the EAS, which refers to the institutional context of the European institutions, characterized by a proper thematic competence and administrative capacity, based on European law and a specific personnel status (Demmke 2015).

On the other hand, within the horizontal dimension of territorial cooperation, the variety and degrees of institutional settings are by far more diverse than it is the case with the more uniform administrative cooperation approaches taking place within settled vertical European inter-institutional arrangements. The range of institutional and organizational solutions at the horizontal level covers loosely coupled single-issue networks, quasi-institutionalized groups, bodies and organs without any legal form/personality, and organizations such as Euroregions with a proper legal status and permanent (seconded or directly recruited) personnel (Zumbusch and Scherer 2015).

Drawing on criteria used in administrative science for the analysis of international public administrations (Bauer and Ege 2016; Ege 2017) an interpretation of the analysis carried out in section 3 of this article, allows for the classification of three ideal-types of ETC-related territorial institutionalism:

Type A stands for a cross-border cooperation approach that is primarily focussed on the joint definition and implementation of individual projects. Actors from either side of the border establish a cooperation structure (in the form of a classical project-organization or even at a lower level of institutionalization in the form of inter-personal or inter-organizational networks) for a limited time, in order to handle a single-issue problem. The project-partners assign the necessary resources for the duration of the project but not necessarily beyond. As only partners do participate that show a strong ownership (otherwise, they would not co-finance the project) and the content is usually clearly pre-defined and limited, the overall degree of autonomy with regards to the institutional capacity of the partners involved is rather low.

Type B in contrast stands for a cross-border cooperation approach that manifest itself via the creation of cross-border bodies. Such bodies need not necessarily have a high level of formal organization (sometimes they are for instance established around a simple convention) and sometimes they are even established with a clearly defined temporal limit (a program-body for instance); but what characterizes them most is the procedural character of their functioning: bodies have the objective to coordinate decision-making processes between partners who in most cases do not assign a thematic competence to the cross-border body but rather a procedural function. Implementing-functions remain with the domestic jurisdictions involved, also resources are allocated only according to limited functions and not to proper thematic tasks. On the other hand, there is a medium degree of autonomy with regard to the functions the body is carrying out: Actors involved act on behalf of their institutional home institution, but may have a relatively marked autonomy with regard to informal “pre-decision-making”.

Type C ultimately stands for the creation of a cross-border organization in the proper sense of the term, which means that the organization has a legal personality to act and it’s (directly recruited or seconded) employees have no temporal restrictions in the sense of fulfilling permanent posts. They can draw on resources which are dedicated to the organizations objectives on a permanent basis. The tasks in question are defined holistically and are fully transferred from the partners to the organization, which has the exclusive competence to implement and – if necessary – develop them further. This is why such an organization has a maximum of autonomy towards its partners – it acts entirely on their behalf.

A high level of institutional organization and the formal transition of thematic competences can contribute to the institutional integration of a given cross-border territory (Lundquist and Trippl 2009) With regard to the last criterion, which is “Institutional integration” from the point of a cross-border territory, it is evident, that there is an increase from Type A to Type C – with the latter standing for the maximum of institutional integration between the different participating jurisdictions in the sense that Type C represents the creation of an independently marked transnational institutional-path.