This article is written by Joachim Beck.

Starting from a perception of cross-border territories being sub-systems, created by the respective national politico-administrative partners involved, the paper asses how cross-border cooperation in Europe can be improved by a new approach of integrated capacity-building.

ABSTRACT

Starting from a perception of cross-border territories being sub-systems, created by the respective national politico-administrative partners involved, the paper asses how cross-border cooperation in Europe can be improved by a new approach of integrated capacity-building. Based on both the achievement but also central challenges that all cross-border territories in Europe are facing in practice, two central fields are interpreted in this regard: training/facilitating and cross-border institution building. The paper concludes that a more effective cross-border policy-making of the future depends on approaches of systemic capacity-builduing and suggests “horizontal subsidiarity” as a new operating principle, to be developed as part of a multi-level governance approach.

1. INTRODUCTION: CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION AS TRANSNATIONAL SUBSYSTEM

Border regions play an important role within the context of European integration: 40% of the EU territory is covered by border regions and approximately 30% of the EU population lives here. Out of the 362 regions registered by the Council of Europe and its 47 member states more than 140 are cross-border regions (Ricq 2006). The effects of the progress of European integration can be studied here: horizontal mobility of goods, capital and people are very obvious in border regions, but also the remaining obstacles to this horizontal mobility. This is why the border regions have often been described as laboratories (Lambertz 2010) and why cross-border cooperation as such can be interpreted as a specific horizontal dimension of European Integration (Wassenberg 2008; Beck/Thevenet/Wetzel 2009).

Beyond this EU-wide dimension, border regions are characterized by a very specific structural situation: natural and/or socio-economic phenomenon like transport, labour market, service-delivery, individual consumption, migration, criminality, pollution, commuters, leisure-time behaviour etc. have typically a border-crossing dimension, directly both affecting and linking two or more neighbouring states in a given trans-border territory. These negative or positive spill-over effects of either structural or everyday policy problems require a close cross-border co-operation between those actors, which are competent and responsible for problem solution within the institutional context of the respective neighbouring state. The wide range of possible inter-institutional and problem-specific constellations in Europe`s border regions, however, does not allow a uniform classification of what the characteristics of this type of regions look like: not all border-regions, for instance, are isolated rural territories facing important structural problems which are ignored by the respective national government. During the last years many border regions have become rather important junctions of the socio-economic exchanges between the neighbouring states and their historical role as “crossing points” has even been positively reinforced (MOT 2007).

One common element of cross-border regions in Europe, however, can been seen in the fact, that cross-border co-operation has a long tradition in the old member states of Europe, and that it was gaining fast significance for the new border regions in Eastern Europe. This history, constant changing institutional challenges and the specific preconditions have in each case lead to the development of specific solutions of the respective cross-border governance (Benz 1999; Benz/Lütz/Schimank /Simonis 2007). In contrast to the national context, where regional co-operation is taking place within a uniform legal, institutional and financial context, cross-border governance is characterized by the challenge to manage working together politico-administrative systems which have a distinctive legal basis and share a different degree of vertical differentiation both in terms of structure, resources equipment and autonomy of action (Eisenberg 2007).

Today, borders are a complex multidimensional phenomenon in Europe (Speer 2010; Blatter 2000; Rausch 1999; Beck 1997). Looking at the realities of living and working environments, as well as the leisure activities of the population (Beck/Thevenet/Wetzel 2009), the horizontal linkages between industry and research (Jakob et al 2010) or the cooperation between politics and administrations (Wassenberg 2007; Kohlisch 2008; BVBS 2011; Frey 2005) etc. it becomes evident, that the border phenomenon and hence the subject of cross-border-cooperation can no longer be restricted to a perception of overcoming functions of territorial separation only (Casteigts 2010; Amilhat Szary 2015). Cross-border areas and the cooperation approaches developed there are specific subsystems (Frey 2003) that are composed of horizontal networking (and selective integration) of functional components provided by the respective participating national (politico-administrative) reference systems. In addition to the spatial dimension, border and cross-border cooperation covers both political, economic, legal, administrative, linguistic and cultural dimensions, which extend the focus of analysis of the specific structural and functionl patterns of the subsystem of ‘Cross-border cooperation’ too (Beck 2010).

Border regions and the cooperation processes taking place within them can be defined today as a separate transnational policy field, whose constitutive characteristics and functionalities in addition to its property as a sub-system of national and regional governance are more and more also determined by the European level. From the point of European integration and the related multi-level perspective it can be observed how cross-border governance has – over time – become a increasingly significant object of European policy (Beck 2011). It is obvious that the cross-border areas of Europe have strongly benefited from the advances of the European integration process. The major European projects such as the Schengen Agreement, the Single European Act (SEA), the Maastricht Treaty or the introduction of the euro in the framework of the Monetary Union implemented important integration steps which have influenced the life of the population in the border regions significantly in a positive way. However, these main European projects border-regions ultimately have not been explicitly defined as object areas, but still must rather be regarded as symbolic fields of application or rather ‘background slides’ of respective high-level European policy strategies. What has impacted, however, and strongly influenced both the emergence and the practical functioning of cross-border cooperation during the last 25 years, is the action–model of European cohesion policy (Beck 2011).

Within the European cohesion policy, only relatively low funding for the promotion of cross-border cooperation was made available until the late 1980s. Yet, the introduction of the Community initiative INTERREG resulted in a veritable thrust. 100 cross-border programme regions have been formed since then and until 2020 29.5 billion€ in EU funds, as well as a nearly great amount of national and regional co-financing will have been invested in border regions. In addition – and alone for the period 2014-2020 – an additional 876 million euros will be invested within the framework of the cross-border component of the neighbourhood policy (IPA-CBC and ENPI-CBC). In these territorial fields of cooperation not only a variety of specific development projects are conceived and implemented jointly between partners coming from different territorial jurisdictions. The general governance model of European regional policy – beyond the narrower project reference – often also leads to optimized structuring of the overall organisation of cross-border cooperation itself.

Between 2000 and 2006 alone, INTERREG III contributed to the creation or maintenance of 115 200 jobs, the establishing of almost 5800 new companies and the program also supported another 3900 already existing companies. More than 544 000 people participated in events, dealing with issues of territorial cooperation. In addition, cooperation within the framework of almost 12 000 networks was promoted, which resulted in the creation of nearly 63 000 cooperation agreements. More than 18 000 km of roads and railways in border areas have been built or repaired, investments in telecommunications and environmental improvements were forced and more than 25 000 specific local and regional initiatives have been promoted. With the 4th programming period (2007-2013), INTERREG became a so-called « mainstream program » of European structural policy, by which cross-border cooperation in addition to the interregional and transnational cooperation has been upgraded as part of the new objective 3 « European territorial cooperation ». Cross-border cooperation processes are thus considered explicit fields of experimentation for European territorial governance and are given an immediate cohesion-related action, which was further strengthened in connection with the objective of territorial cohesion, newly introduced in the Lisbon Treaty. The current program period (2014-2020) is characterised by a stronger thematic focus in programming as well as a more intensive impact-orientation when choosing and implementing new cross-border projects (Beck 2011; Ahner/Füchtner 2010).

An interesting pattern is finally the personnel capacity that has been developed within the context of European territorial cooperation over time. In the absence of reliable data only an estimation can be done here. One established method to calculate the personnel-needs for an administrative unit – in the absence of quantitative figures – is to develop a realistic vision about the administrative overhead (measured in Full time equivalents – FTE) required per million inhabitants (Hopp/Göbel 2008, p. 329). Applying this method to the context of territorial cooperation, a pilot survey carried out by the author among members of the TEIN-Network , came to the result, that – for the case of cross-border cooperation – an average total administrative overhead relation of 55 FTE/one million inhabitants of a cross-border territory can be realistically assumed . This indicator can be used for an extrapolation of the administrative CBC capacity at the level of the entire European territory: Based on the assumption, that at NUTS 2-level 150 million EU inhabitants (e.g. 30% of the EU population) are living in border-regions, one can extrapolate a total direct horizontal administrative capacity of 8.250 FTE. Adding a calculated permanent capacity generated at project level (12.826 FTE), the total number of independent horizontal cross-border capacity would thus amount up to 21.076 FTE’s (Beck 2017). The overall horizontal capacity of the entire European territorial cooperation, however, would be certainly significantly higher, as this figure is only a conservative estimation for the narrower range of cross-border cooperation at contiguity level, letting aside the many forms and levels of transnational co-operations taking place with or without EU funding. Yet, the permanent personal capacity of European territorial cooperation at cross-border level alone represents nearly half of the personnel-capacity of the European institutions in Brussels.

Beyond these achievements, cross-border co-operation is still confronted and finds itself sometimes even in conflict with the principle of territorial sovereignty of the respective national states involved (Beck 1999). Even legal instruments aiming at a better structuring of the cross-border co-operation by creating co-operation groupings with a proper legal personality (Janssen 2007), like for instance the newly created European Grouping of Territorial Co-operation (EGTC) , do not allow an independent trans-national scope of action: regarding budgetary rules, social law, taxation, legal supervision etc. the details of the practical functioning of an EGTC depend fully on the domestic law of the state, in which the transnational grouping has finally chosen to take its legal seat.

Even in those regions where the degree of co-operation is well developed, cross-border co-operation is also still a transnational politico-administrative subsystem, created by and composed of the respective “domestic” national partners involved. Both, institutions, procedures, programmes and projects of cross-border co-operation depend – in practice – on decisions, which are still often taken outside the closer context of direct bi- or multilateral horizontal co-operation. In most transnational constellations – also where federalist states are participating – cross-border policy-making can not be based on a transparent delegation of proper competences from the domestic partners towards the transnational actors, but the domestic partners must still rather recruit, persuade and justify their actions and their legal and financial support for each and every individual case. The “external” influence on such a sub-system of co-operation has, thus, to be considered as being relatively important. Cross-border co-operation can therefore be interpreted as a typical principal-agent constellation (Czada1994; Chrisholm 1989; Jansen/Schubert 1995; Marin/Mayntz 1990): with the principals being the national institutional partners of this co-operation (regions, state organisations, local authorities etc.), representing the legal, administrative, financial and decisional competences and interests of their partial region, and the agents being the actors (cross-border project partners, members of transnational bodies or specific institutions, programme officers and co-ordination officers etc.) responsible for the preparation, the design and the implementation of the integrated cross-border policy (Beck 1997). Different zu classical principal-agent assumtions, however, the principals are playing a much mor important role, clearly defining the scope and limits of action for the agents within a transnational context of such a “small foreign policy”.Cross-border co-operation thus has always both an inter-institutional and an inter-personal dimension, requiring the co-operation of both, corporate and individual actors with their specific functional logic, motivated by special interests in each case (Coleman 1973; Elster 1985; Marin 1990).

The reference level of this sub-system is founded through a perception of cross-border regions as being “functional and contractual spaces capable of responding to shared problems in similar and converging ways, so they are not political regions in the strict sense of the term” (Ricq 2006, p. 45). On the other hand, the fact that cross-border co-operation is not replacing, but depending on the competence and the role of the respective national partners (Blatter 2000; Rausch 1999) does not automatically mean, that this co-operation is a priori less effective than regional co-operations taking place within the domestic context. Research on multi-level policy-making in Europe has shown, that a productive entwinement and networking of different actors coming from distinct administrative levels and backgrounds can be as effective as classical institutionalized problem-solving (Benz 1998; Benz/Scharpf /Zintl 1992; Grande 2000). Yet, the institutional and functional preconditions of cross-border co-operations are far more complex and exposed to various conditions. The central criterion for the evaluation of a successful cross-border governance, however, is, nevertheless, both the degree of mobilisation and participation (structure and quality) of the relevant institutional and functional actors and the effectiveness of the problem-related output which this subsystem of co-operation is producing (Casteigts/Drewello/Eisenberg 1999).

2. PRACTICAL CHALLENGES OF CROSS-BORDER GOVERNANCE – A NEED FOR CAPACITY BUILDING

In light of the impressive career of the governance concept in Social Sciences (see Blatter 2006), Governance is today one of the central concepts being discussed in the practical and theoretical field of cross-border cooperation too. However the definition of the term governance is quite often not clear in its use. It seems therefore useful to have a closer look on its initial conceptual definition first, before presenting in more detail the specific patterns of cross-border governance.

In its more generic definition, governance refers simply to the different mechanisms which generate order within a given population of actors in a specific policy-field. This can happen through unilateral adaption (market), command and obedience (hierarchy), negotiation and functional interaction (networks) or through a common orientation of behaviour based on generalized practices of a society (norms, values) (Mayntz 2009: 9).

Following Fürst (2011) a second analytical dimension must be distinguished in this respect: the procedures that lead to such collective order (decision processes, rules of decision making, styles of policy-making) which can be defined as governance in the narrow sense of the term and the different forms of how these processes are organized (classical institutions versus non-hierarchical networks), which can be defined as government in the narrow sense of the term.

According to Beck/Pradier (2011) a third analytical component can be added, in order to fully exploit the concept of governance, and which seems very important especially from the point of view of territorial development: this is the practical shaping of governance. Two dimensions must be distinguished in this regard, the horizontal dimension which refers to the types of actors involved (governmental, non-governmental, society, private) and the vertical dimension which refers to the different territorial levels involved (local, regional, sub-national, national, European).

Cross-border governance is characterized by a number of features that represent a distinctive pattern compared to aclassical „mono-jurisdictional“ approach (Beck/Pradier 2011): The first distinctive feature is that cross-border governance initially always has a territorial dimension (Casteigts 2010). The observed cooperation and coordination processes are constituted within a spatial parameter including areas of different bordering countries. Each given cross-border spatial context (eg presence of natural boundaries, population density, degree of socioeconomic integration, polycentricity) determines the resulting challenges to be matched with regards to the production of joint spatial solutions (development given potentials, creating infrastructure conditions, complementarity of sub-regional spatial functions, etc.) and thus constitutes the functional framework of this type of cooperation. Characteristically, however, the territorial dimension of cross-border cooperation has a strong inter-relation with the given politico-administrative boundaries which makes is more difficult to handle socio-economic spill-over effects that typically exceed these limits. This creates the challenge of adapting the spatial parameters of the cooperation to the scope and content of different levels of functional integration, with the practical difficulty that a “regional collective” (i.e. the mobilization/integration of all relevant intermediary actors of a territory) is hardly emerging on a cross-border basis, which is a distinct pattern compared to “classical” regional governance taking place within a single domestic context (Kleinfeld/Plamper/Huber 2006).

The second feature of cross-border governance is that this type of regional governance takes place within a context that involves relations between different countries. The transnational dimension of cross-border governance is a specific characteristic, which greatly contributes to the explanation of the specific patterns and functionalities of this cooperative approach. Unlike « classic » regional governance, transnational governance is characterized by the fact that decision arenas of different political and administrative systems have to be inter-connected. The challenge for the resulting cross-border bargaining-systems, however, is not only to coordinate different delivery-mechanisms of different politico-administrative systems but also to manage the complex “embeddedness” of the cross-border territorial sub-system into the respective national politico-administrative systems (Frey 2003). In addition, the intercultural mediation and communication function, which is also closely linked to the transnational dimension of cross-border governance, is a real source of complexity. This refers not only to the interpersonal but also to the inter-institutional components of the cross-border negotiation system and includes the open question about the possibilities and limits in matching divergent administrative cultures in Europe (Beck/Larat 2015). Finally, features such as the strong consensus-principle, the delegation principle, the non-availability of hierarchical conflict resolution options, the principle of rotation of chairs in committees, the tendency to postpone decisions rather than implementing them can also be explained by this transnational dimension. Cross-border governance obviously shares largely general features which were highlighted in the research on international regimes and which reflect (dys)functionality of transnational bargaining systems. At the same time this allows to explain, why it is sometimes so difficult for cross-border actors to agree on even the very basic components of the governance approach: terms such as « actors », « networks », « decision rules », « civil society », « project », “cluster” etc in fact represent deeply culturally bound concepts upon which inter-cultural differences and conflicts very quickly can arise (Eisenberg 2007).

The third distinctive feature of cross-border governance can be seen in its European dimension (Lambertz 2010). Stronger than national patterns of regional governance, which also may refer to European policies, especially when incorporating issues like external territorial positioning strategies and / or the use of appropriate European support programs, the characteristics and finalities of cross-border governance are much more interlinked with the project of European integration as such. Cross-border territories are contributing a specific horizontal function to the European integration process (Beck 2011). European notions, objectives and policy approaches such as « Europe is growing together at the borders of Member States « , « Europe for Citizens », « territorial cohesion » or « European Neighborhood Policy « are concepts that relate directly to the European dimension of cross-border cooperation. Cross-border cooperation today is a specific level of action within the European multi-level context. Accordingly cross-border territories have a (sectoral) laboratory function for the European integration: in all these policy areas that are either not harmonized at European level or where European regulations on the national level are implemented differently, practical solutions and answers to real horizontal integration problems have to be developed in a cross-border perspective. This represents a specific innovation perspective for European integration, taking place at the meso-level of cross-border cooperation. In addition, the Interreg program with its characteristic, “externally defined” functional principles, is determining the cross-border governance to a large extend. This European action model characterizes the cooperation in general much stronger than it is the case within the national context, where also other than European funding opportunities (i.e. national programs with much less administrative burden) do exist.

The fourth feature of transnational governance can finally be seen in its thematic dimension. Cross-border cooperation consists of more or less integrated approaches of cooperation between different given national policy areas. The character of these regulatory, distributive, redistributive or innovation-oriented policies not only enhances the respective constellation and the corresponding degree of politicization of the factual issues in question; it also determines crucially different institutionalization requirements of the governance structures (Beck 1997). These may vary considerably by policy field, and make it very difficult, to develop an integrated, cross-sectoral governance-approach at the cross-border level. The complexity of such governance is increased by the fact that the (variable) policy types may determine the interests and strategies of the actors involved directly, thus also affecting the interaction style, the applied decision rules, and ultimately the efficiency of cross-border problem-solving significantly. The difference to the functionality of collaboration patterns that take place within a single institutional system context must be seen in the fact, that the systemic determinants and thus the intersection of actors, decision skills, resources for action and the synchronizing strategic interests in the cross-border context can vary widely by policy-field and the different institutional partners involved. Thus, constellations of action and actors, which are evident within the national context and which allow for the development of « social capital » and a constructive and productive problem-solving within a specific territorial/or sectoral governance approach are often completely different in the perspective of a cross-border governance. This leads to very specific patterns of cross-border (non-) policy-making, which is characterized by much higher complexity and informal dynamics of the processes on the one hand and a decoupling of thematic and interest-related interaction on the other, and which have therefore been described as a specific pattern of transnational administrative culture (Beck / Larat 2015).

The horizontal analysis of the contributions of a joint research project, carried out by the Euro-Institute and the University of Strasbourg with more than 100 contributions coming from both the academic field and from practitioners of cross-border cooperation (Wassenberg 2010; Wassenberg/Beck 2011a, 2011b, 2011c; Beck/Wassenberg 2012a, 2012b) allowed to identify two generalized patterns of cross-border-policy-making in Europe. One first conclusion that we were able to formulate on this basis (Beck 2012a) is the hypothesis of a certain convergence with regards to the practical functioning of cross-border cooperation in Europe. This convergence is mainly caused by the procedural logic of the financial promotions programmes of the European Commission with regards to the ETC objective (“Interreg”) leading to more or less unified practices regarding the implementation of elements like the partnership-principle, the principle of additionality, multi-annual programming based on SWOT-analysis, project-based policy-making, project-calls, financial control etc. As a consequence we can observe during the last two decades or so a general pattern of CBC policy-making that is characterized by a shift from informal exchanges to more concrete projects, from general planning to attempts for a more concrete policy- implementation, from rather symbolic to real world action, from closed informal networks to more transparent and official institutions.

In addition the role and the perception of the very concept of the border has changed considerably: the separating function is less important today but more and more replaced by an integrated 360° perception of the cross-border territory and its unused potentials. At this level it is not so much the impact of the European programmes and their sometimes a bit too ambitions objectives as such, but rather the change in the perception of the local and regional actors themselves, which after years of sometimes frustrating experiences, leads to a certain positive pragmatism when it comes to cross-border issues: it becomes more and more evident, that cross-border institutions today are more platforms than real administrative units, allowing for the very pragmatic search for joint solutions to common local problems resulting from the increasing border-crossing socioeconomic dynamics (Beck/Thevenet/Wetzel 2009), in areas such as transportation, spatial planning, environmental protection, risk prevention, citizens advice and health cooperation, etc. rather than for the definition and implementation of big strategic ambitions.

The research project has on the other hand allowed to identify a second general pattern, which is represented by seven central challenges of CBC policy-making, determining and often still hindering – however with differences regarding their intensity and combination – the horizontal interaction in cross-border territories everywhere in Europe:

- Developing functional equivalences between different politico-administrative systems: How to develop functional interfaces that allow for successful cooperation between partners coming from different institutional domestic backgrounds with regards to distribution of power and resources, professional profiles and sometimes even the scope and the legitimacy for transnational action as such (Beck 2008)?

- Creating effective knowledge-management for the cross-border territory: How to generate and use valid information about the characteristics, the real world problems but also the potentialities of a cross-border territory in a 360° perspective, how to base future action on a sound and integrated empirical basis and thus avoiding a negative “garbage can model” (Cohen/March/Olsen 1972) practice of cross-border policy making (ad hoc solutions developed by individual actors, based on individual preferences in search for an ex post justification and a real world problem).

- Transferring competencies from principals to agents: How to reduce the dependency of cross-border actors and policy-making on the respective domestic context by identifying fields of cross-border action that best can be implemented by a transfer of real administrative and functional competence from the national jurisdictions towards cross-border bodies with sufficient administrative, financial personnel capacity, how to design decision-processes in this regard (Benz/Scharpf/Zintl 1992)?

- Optimizing the interaction between actors: How to turn the confrontation of different cultures, attitudes, expectations, assumptions, values, interests etc into a productive working context, which allows for the avoidance of mutual blockages and the development of innovation and real added-values instead (Demorgon 2005; Eisenberg 2007; Euro-Institut 2007); how to integrate actors representing different sectors (public, private, societal) and cultures into existing patterns and structures of cooperation, how to create and manage inter-sectoral synergies in a cross-border perspective (Beck/Pradier 2011)?

- Finding the right level of organization and legal structure: How to find the right degree of institutionalization and the right legal form for different cross-border tasks by developing a good balance between open network and classical organizational approaches when structuring the cross-border working context; how to avoid both the case of institutional sclerosis and informal/individual arbitrariness (Beck 1997)?

- Capturing and measuring the value added and the territorial impacts: How to pre-assess cross-border impacts of different policy-options before taking action on the preferred one; how to develop and inform specific indicators allowing for a better demonstration of the specific value added of the integrated cross-border action compared to an action taken by the neighboring jurisdictions separately (Tailon/Beck/Rihm 2011)?

- Increasing the sustainability beyond a simple multi-project approach: How to avoid the case of multiple uncoordinated sectoral projects which creates fragmented cross-border activity for a certain time (funding) period only, by strengthening the target-orientation and selectiveness of cross-border policy-development based on integrated (eg. inter-sectoral) territorial development strategies (Casteigts 2010).

It is evident, that the seven challenges cited above are at the same time the central fields for any capacity-building approach responding to the needs of a future multi-level-governance perspective of cross-border cooperation (Scharpf 1994; Beck/Pradier 2011; Jansen/Schubert 1995; Nagelschmidt 2005; Beck/Wassenberg 2011). This includes not only the question of how individual actors or members of institutions can better be trained in order to cope with these challenges. Rather the overall systemic question is on the agenda, e.g how the entire cross-boder cooperation-system can be improved and professionalized in order to reach a new level of quality which allows for a better development of the endogeneous potentials of this type of territory within the context of the overall objective of territorial cohesion in Europe (Frey 2003).

It is amaizing to see, how the well known and very basic definition of the concept of « capacity-building », developed by the UNDP within a rather different context, can inspire such a reflexion on the future of cross-border pilicy-making in Europe. According to UNDP (2006), capacity-building or capacity-development « …encompasses … human, scientific, technological, organizational, institutional and recource capabilities. A fundamental goal of capacity-building is to inhance the ablility to evaluate and address the crucial questions related to policy choices and modes of implementation among development options, based on an understanding of environment potentials and limits and of needs perceived by the people of the country concerned » (UNDP 2006, p.7). Accordingly, capacity-building has to cover three levels : a.) the creation of an enabling environment with appropriate policy and legal frameworks, b.) institutional development, including community participation and c.) human resources development and strengthening of managerial systems.

As these three elements refer directly to the seven challenges of cross-border cooperation identified above I suggested in this article, to better exploit the concept of capacity-building within the context of cross-border cooperation in Europe.

3. TRAINING/FACILITATION AND INSTITUTION-BUILDING : TWO FIELDS OF CAPACITY-BUILDING FOR CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION

Border regions everywhere have specific characteristics. A wide range

of social and economic phenomena have a ‘border crossing’ dimension ,

in areas as different as transport, labour markets, service delivery,

consumption patterns, migration, criminality, pollution, commuter

movements, tourism and leisure time activities. All of these require

close cross-border cooperation between neighbouring states. However

unlike in the national context, where regional cooperation takes place

within a uniform legal, institutional and financial framework,

cross-border cooperation faces the challenge of managing different

politico-administrative systems which have a distinctive legal basis and

are usually characterised by different degrees of vertical

differentiation in terms of structures, resources and autonomy of action

(Casteigts 2010; Beck 1997; LANG 2010).

After a long post-war

experience, where cross-border-cooperation was mainly marked by izs

reconsiliation function (Böhm/Drápella 2017) we are now in Europe on the

threshold of cross-border cooperation of a completely new quality (Beck

2011). With the new cohesion policy of the European Union, attaching

much greater importance to territorial cohesion and the extent of real

impacts of cross-border actions (Tailon/Beck/Rihm 2011), but also thanks

to a new generation of actors (Botthegi 2012), who are more interested

in results than procedures, many border territories are currently

redesigning and trying to strengthen their given pattern of cooperation

(Casteigts 2010). At the same time, cross-border cooperation should

continue to be developed and enhanced by a capacity building

structurally and functionally, so that it is up to the real importance

of border territories for the future European integration process

(Jakob/Friesecke/Beck/Bonnafous 2011). Two practical fields seem of

particular importance in this respect : strengthening

training/facilitation and further developing the institutional capacity

of cross-border cooperation.

3.1 TRAINING / FACILITATION : THE EURO-INSTITUTE APPROACH

One of the key bottlenecks preventing the deepening of cross-border cooperation in Europe is the lack of knowledge and understanding of the political and administrative systems of the neighbouring countries. A successful cross-border cooperation needs qualified actors who are able to close the gap between the subsystem and its specific functional characteristics and the functional preconditions provided by the different domestic juristictions involved (Jann 2002; Beck/Thedieck 2008). One approach, which has been very successful for over 20 years now, is the creation of a specific institution, which exclusively works on CBC training – the Euro-Institute Kehl/Strasbourg (Beck 2008b). This bi-national institution contributes to the improvement of cross-border cooperation by continuing education and training and provides practical advice and coaching to practitioners in the cross-border field. In this way, the Institute has become a facilitator for successful cross-border cooperation in the Upper Rhine region and in Europe with regard to public policies, and contributes actively to the resolution of problems resulting from different legal and administrative systems.

The Euro Institute`s training product is structured according to the needs identified by the actors involved in cross-border cooperation. The main characteristic of this product is its bi-national and bicultural orientation, and the main target groups are the employees of the state and local administrations in Germany, France and increasingly Switzerland. Its training courses are also open to participants from the private sector, and from research institutions, universities, civil society associations and other groups.

Based on the Euro-Institute’s experience, training in a cross-border context as part of an overall capacity-building approach should develop at least three levels of personal skills:

Basic training on cross-sectoral competences

The basic component of such a training approach is the development of the cross-sectoral skills and competences necessary for any cross-border and/or inter-regional cooperation. The main objective here is to provide those involved with the necessary institutional and legal knowledge about the politico-administrative system of the neighbouring states and about the system of cross-border cooperation itself. In addition, the relevant instrumental, methodological and linguistic skills must be trained in order to prepare and structure the proposed cross-border activity in advance. It is very important to sensitise the future actors about the importance of the intercultural factor and to provide them with the necessary tools and methods of intercultural management. Curses should also provide participants with the specifics of managing cross-border projects in terms of planning, financing, organisation of meetings, and monitoring and evaluation.

The courses and qualifications provided under this first level meet an increasing demand at our Institute. The more cross-border cooperation becomes an everyday reality, the more new actors face the challenge of becoming better trained and qualified in terms of the skills the course covers. Nearly all public institutions in the Upper Rhine valley are now seeking well qualified people who can represent them in both formal and informal cross-border cooperation situations.

Specialised training

A cross-border training programme should then also provide specialised training courses which are more oriented towards representatives from the different administrative sectors in the neighbouring states. The content of these courses consists of selected policy-oriented topics within cross-border cooperation. The aim is to provide a neutral platform for exchanges between specialists from the different countries so that they can better understand the specific sectoral competences and organisational structures in the other countries, and identify differences and similarities with their own – or just allow them to get current information and analysis on policy developments and good practice in the neighbouring state. At the Euro-Institute, this training mainly consists of two day seminars, including informal exchanges during an evening event on the first day. As most cross-border problems have a sectoral or thematic component, and thus require cooperation between the relevant sectoral services, these specialist seminars are very often the starting point for future joint projects, and sometimes even lead to the establishment of bilateral or trilateral standing working groups.

A specific programme deals for instance with cooperation between the French and German police, justice and gendarmerie services in the context of the Schengen treaty. This programme, which consists of five annual seminars, was established in 2004. It is accompanied by a steering committee of high-level representatives from the participating administrations which select the topics and annually evaluate the course, which has been developed by the Euro Institute.

Developing competences on European affaires for local and regional authorities

At a third level, it seems necessary to enhance the capacities of national public administrations with regards to European integration. Most local and regional administrations take a very pragmatic view and see Europe mainly as an opportunity to access EU financial support programmes like INTERREG. This is a legitimate position which raises numerous practical questions: how to find the right partner across the border; how to fill in the application form; how to set up a project’s organisation; how to manage a cross-border budget; how to justify expenses; how to define good progress and impact indicators, and how to make a project-oriented monitoring and evaluation system work. Although the INTERREG secretariats of the relevant Operational Programmes usually do a very good job, practical experience shows that local and regional partners are very often overloaded by the complexity of the reporting and accounting demands, imposed on them by the funder. In addition, project partners coming from different jurisdictions often have different perceptions of these demands, and have to deal in the day-to-day running of a cross-border project with national administrations with quite different administrative cultures. This is why the Euro Institute, using its own extensive experience of such projects, provides adaptable practical coaching to both the individual project leader and the bi- or tri-national project teams as an intercultural group. This contributes to the smooth functioning of the project teams, helps to avoid blockages, and thus facilitates both project and programme implementation.

Under the EU-objective of territorial cohesion, more and more local and regional authorities want to participate in inter-regional or even trans-national projects, and are developing partnerships with other European regions. In this context the question of good practice in international network management arises: how to build and maintain a solid international partnership; what is the relative position of the actors in the network; how to prepare and manage international meetings and so on. Here the Euro Institute also provides practical assistance.

Last but not least, the local and regional authorities are increasingly realising to what extent they are affected by European legislation. The fact that in Germany, for example, 70% of all local administrative action is more or less determined by EU law, rises the question of how to become more actively involved in the preparation of this law and how to better represent local and regional interests in its formulation. Based on the wide practical experience of its former Director, who has since 2004 been an accredited trainer on Impact Assessment for the European Commission’s Secretariat General, the Institute helps local and regional actors to become more familiar with the relevant procedures at EU-level and teaches them how to contribute actively to stakeholder consultations and ex ante impact assessments, which increasingly have to consider regional and/or trans-regional dimensions.

A thorough knowledge of the politico-administrative system of the neighbouring country is a prerequisite for any efficient cross-border cooperation. The main difference of the Euro Institute’s training courses compared with those of a national training organisation is therefore a real concentration on themes arising out of the needs of the cross-border professionals within the various sectors. Also the fact, that the training courses are always inter-service, bi-national and bilingual in nature has contributed to their high acceptance among participants. We have found that partnerships between the relevant administrations are best developed when the courses are prepared by an ad hoc group of different national specialists. Such preparation requires a lot of time and investment by the partners – but it is a necessary precondition for any effective bi-national training product, which not only considers the intercultural dimension but actively uses it in terms of content, methodology and participation. For successful cooperation with no ‘mental frontier’, trainers too must understand that they have to reconsider their whole way of thinking, recognising that constructive cooperation is not possible without knowing and respecting the structures, working methods and ethos of the neighbouring country’s system – as well as fully understanding one’s own!

The contribution of the Euro Institute in making this partnership principle really work is twofold: providing a neutral platform, and facilitating intercultural and inter-service exchange. Most important in this respect is a strategic positioning which is able to respond quickly to the real needs of the participants. Sometimes this means to be modest in one’s aims and to provide only technical and logistical support. However, the provision of methodological and linguistic competence along with solid experience of good practice in intercultural management (Hall 1984; Hartmann 1997) are the hallmarks of the Euro Institute (Euro-Institute 2007).

The success of this Euro-Institute approach has recently lead to the creation of a new European actor: the transfrontier Euro-Institut-network (www.transfrontier.eu) aiming to built up training capacity on cross-border questions at a EU-wide level. 12 partner-institutions coming from 9 different cross-border contexts all over Europe decided to propose a coordinated answer to the increasing need for knowledge, competences, tools and support on cross-border affaires. Regarding the rising awareness of the importance of cohesion policy in Europe, the idea of the Network is to build capacities in cross-border and transfrontier contexts and this way strengthening the European integration. In order to achieve this goal and to have an extensive overall view of the territorial specificities in Europe, the project coordinator has been careful to invite partners from different parts of Europe to participate in the project. Hence, the partners involved in this project come from “maritime borders”, “old European borders”, “new eastern borders”, “peace keeping borders”, “external borders”, as well as “overseas borders between outermost regions”. As such, the partnership will be able to gain a comprehensive overview of the need for the professionalization of actors in cross-border cooperation and also gain insight into the current situation regarding transfrontier cooperation.

The TEIN gathers training organizations and universities and aims at facilitating cross-border cooperation and at giving concrete answers to the need of Europe for professionalizing actors on transfrontier issues. The “identity and reference grids” of all the partners testify from the quality and the great experience of each partner. The partners of the TEIN exchange best practices, analyse the specificity of training and research on cross border issues/in cross border contexts, capitalize on and draw synergies from the different local initiatives, work on new products like transferable training modules (training for cross-border project managers, etc.), methods (need-analysis methods in cross-border regions, etc.), tools (impact assessment toolkit, etc.), produce valuable research in this field and assure that newest research results within this field are disseminated to actors involved in transfrontier cooperation. TEIN will develop a joint certification system for cross-border training in Europe and will also enable bilateral projects in fields of common interest (exchange of learning units, of lecturers, common research programme, involvement in conferences, etc.) and an increased knowledge and awareness of cross border issues (at local, regional, national and European level) by producing higher quality work in this field.

3.2 CROSS-BORDER INSTITUTION BUILDING AS CHALLENGE

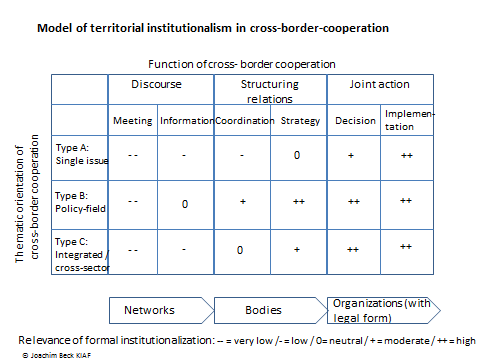

With regard to the functional task-focus, practical cross-border cooperation approaches in Europe are covering a wide range of material fields of action. Depending on the respective territorial context, these cover classical fields of regional development (such as spatial – and urban development planning, economic development, research and development, transport etc.), specific approaches of cooperation in sectoral policy areas (health, social security, education and training, science and research, environment, conservation and tourism, etc.) or areas of public services of general interest (supply and disposal, security, infrastructure, leisure and sport etc.). A classification of these various tasks, as relevant for the question of the challenge of cross-border institution-building, can be developed on the basis of the dimensions of « thematic orientation » and the characteristic « functional role“ cross-border-cooperation is de facto providing.

Regarding the criteria of thematic differentiation a task-classification can lead to the following typology (Beck 2017):

Type A: Cooperation within the framework of mono-thematic projects (bridges, bike paths, bus-lines, kindergardens, information services for citizens, businesses, tourists, etc.) including INTERREG-life-cycle management (« single issue »);

Type B: Cooperation within entire policy-fields (environment, health, transport, education, science and research, etc.) (« policy-related »)

Type C: Cross-topic cooperation like programming/implementation/management of INTERREG programme; cooperation taking place within political bodies such as government commissions, Euroregions, Eurodistricts; Inter-sectoral cooperation taking place within the framework of innovative networked governance approaches of territorial development (« integrated-cross-sectorial »)..

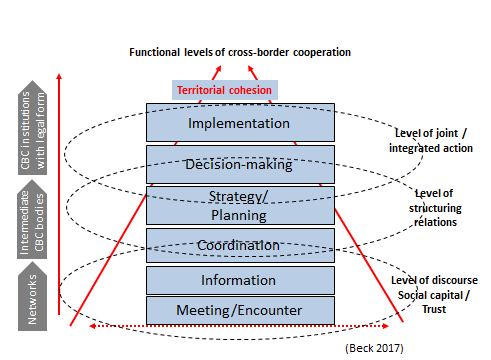

In contrast, the typology of the criteria of « functional role of cooperation » refers to a variation in the intensity of cooperation requirements and the related performance of duties and tasks. Six ideal types of functional levels of cross-border cooperation can be identified here, that build on each other in practice – in the sense of a core process – and which are very often sequentially interlinked in the sense of different stages of development: Type 1: The encounter between actors from various national political and administrative contexts can be considered as a basic function of the cross-border tasks. The aspects of mutual learning and the exchange about the respective specifications of the home context mark this level. Mutual meeting promots mutual understanding and thus forms the basis for building trusting reciprocal relationships.

Type 2: On this basis, the partners can then enter into the second phase, which is characterized by a regular mutual information.

Type 3: Once informative cross-border relations are sustainable, these lead to the cross-border coordination of the relevant actions and policies of the partners involved in the third step.

Type 4: From this, the demand to develop joint cross-border planning and strategies that can ensure a coordinated, integrated approach in relevant fields arises as a fourth level.

Type 5: On this basis, then joint decisions can be made, which eventually lead to

Type 6: Shared, integrated and coordinated cross-border implementation of tasks on a sixth level.

This classification of six cross-border functional levels, building on each other, stands for the empirical observation that both the intensity, the liability, as well as the integration of the cooperation growths from one level to the other. Each stage itself represents a necessary and legitimate dimension and precondition of the effective fullfillment of cross-border tasks. In addition, the six levels are also representing different logics of interaction between the actors involved: while the first two levels are primarily a level of discourse, the following two stages foucs rather on the structuring of the relations of interaction as such whereas the last two levels refer to implementation-related joint actions in a transnational context. Accordingly a reliable cross-border task-fullfillment is therefore only given (and possible) if all functions in all six reference levels are realized. The observation, that the two functions « decision » and « implementation » often still show empirical deficits (Beck/Pradier 2011) illustrates the challenges regarding the state of implementation of an integrated cross-border policy in many cross-border constellations.

The following figure summarizes the model of different functional levels of cross-border cooperation:

cooperation of the new generation tries to increasingly promote

integrated development of cross-border potentials (Ahner/Füchtner 2010).

Thus the question, by which means of institution-building this

territorial development can best be accomplished, is more and more on

the agenda in many border regions. Institutions can be understood as

stable, permanent facilities for the production, regulation, or

implementation of specific purposes (Schubert/Klein 2015). Such purposes

can refer both to social behavior, norms, concrete material or to

non-material objects. Following the understanding of administrative

sciences, institutions can in this way be interpreted as corridors of

collective action, playing the role of a “structural suggestion” for the

organized interaction between different actors (Kuhlmann/Wollmann 2013,

p.51). The question of the emergence and changeability of such

institutional arrangements in the sense of “institutional dynamics”

(Olson 1992) is subject to a more recent academic school of thinking,

trying to integrate the various mono-disciplinary theoretical premises

under the conceptual framework of neo-institutionalism. Following

Kuhlmann/Wollmann (2013, pp 52) three main theoretical lines of argument

can be distinguished here:

Classical historical neo-institutionalism

(Pierson 2004) assumes that institutions as historically evolved

artefacts can be changed only very partially and usually such change

only takes place in the context of broader historical political

fractures. Institutional functions, in this interpretation, impact on

actors, trying to change given institutional arrangements or develop

institutional innovations, rather in the sense of restrictions. The

classical argument here is the notion of path-dependency. In contrast,

rational-choice and/or actor-centered neo-institutionalism (Scharpf

2000; March/Olsen 1989) emphasizes the interest-related configurability

of institutions (in the sense of “institutional choice”), however, the

choices that can realistically be realized depend on the (limited)

variability of the existing institutional setting. Approaches of

sociological neo-institutionalism (Edeling 1999; Benz 2009), on their

turn, also basically recognize the interest-related configurability of

institutions, however – rejecting the often rather limited model in

institutional economics of a simple individual utility maximization of

actors – emphasize more on issues like group-membership, thematic

identification or cultural adherence as explanatory variables for the

characteristics of institutional patterns.

With regard to the

conceptual use of neo-institutionalist thinking, territorial cooperation

represents a twofold interesting application area. First it constitutes

a object-based framework, to which the three above lines of argument

are related: the territorial reference-frame of politics, in which

institutional arrangements are de facto materializing themselves.

Second, territorial cooperation itself, as dependent variable, can only

be understood rightly, if – with regard to its genesis, structural and

procedural functioning and material effectiveness – both the historical,

actor-centered and sociological factors are considered as explanatory

variables, taking into account their respective interdependency. The

related research question here would refer to the functionality of

different degrees and arrangements of such territorial institutionalism

from the point of the partners involved: What institutional functions

are delivered and/or expected and where can they be situated within the

continuum of loosely coupled (inter-institutional and inter-personal)

networks in the sense of a „transnational governance“ on the one hand

(Benz at al 2007; Blatter 2006) and more formal, institutionally

solidified organizational structures in the sense of a “transnational

government” on the other hand (Fürst 2011; König 2008, pp. 767; König

2015, pp. 216ff).

The basic reference points of such patterns of

European territorial institutionalism are the related territorial

cooperation-needs, which are in turn derived from the different thematic

and functional tasks of territorial development itself and which can be

understood as intervening variables of such forms of institutionalism:

Different degrees of cooperative institutionalization, such would be the

related hypothesis, can be interpreted as a territorially influenced

function, resulting from the collective adjustment between different

historically evolved and thus still rather persisting national systems

(public administration, law, political, economic and social order,

characterized by diverging functionalities), the interest-related

interaction between the actors involved (local communities, territorial

governments, enterprises, associations, universities etc. with

individual institutional interests), and the cultural and group-related

formations (administrative and organizational cultures, norms, leading

ideas, mental models etc. of both the collective and individual actors)

which are finally, in turn, impacted/influenced by a (interdependent)

intervening territorial variables such as geographical location,

socio-economic situation, the practical handling of functional

development needs, policy-typologies and/or policy-mix, inter-cultural

understanding (for further explanantion see: Beck 2017a).

The fact of

different interests and systems meeting each other within the subsystem

of cross-border cooperation marks both the complexity and the

conditions under which joint institutional solutions can be developed

cooperatively. Referring to the above described typology of CBC-tasks

and functions, in principle, the need of institutionalization would

depend on and increase in relation with the expanded level of both the

tasks and the functions to fullfil. Following Beck (1997; 2017), Blatter

(2000) and Zumbusch/Scherer (2015) the following figure suggests a

model of territorial institutionalism in cross-border cooperation:

4. CONCLUSION : SETTING THE FRAME FOR A SYSTEMIC CAPACITY-BUILDING OF CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION

In addition to training/facilitation and territorial institutionalism, which have been outlined in more detail above, four further components of a systemic cross-border capacity-building seem to be of particular strategic interest for the future:

Strengthening the evidence base of cross-border policy-making: One central weakness of most cross-border policy-making consists in the lack of tangible base-line information regarding both the real world strengths/weaknesses and the potentials of the cross-border territory in question. The national and regional statistics often suffer from a lack of comparability and specific analysis on the characteristics and the magnitude of the socio-economic cross-border phenomenon (be it mobility of citizens, economic exchanges and relations, transport and traffic movements, exchanges between universities, students, associations etc) suffers both from the challenge of quantification and qualification. In addition, the results of the SWOT-analysis carried out at the beginning of a new programming period, are often not really binding later on, when the selection of project applications actually takes place. In turn, both the programme and the project level have difficulties to describe and capture the specific cross-border added-value of the actions that were funded – mostly due to the absence of credible impact-indicators and a data generation that requires specific qualitative and quantitative methods.

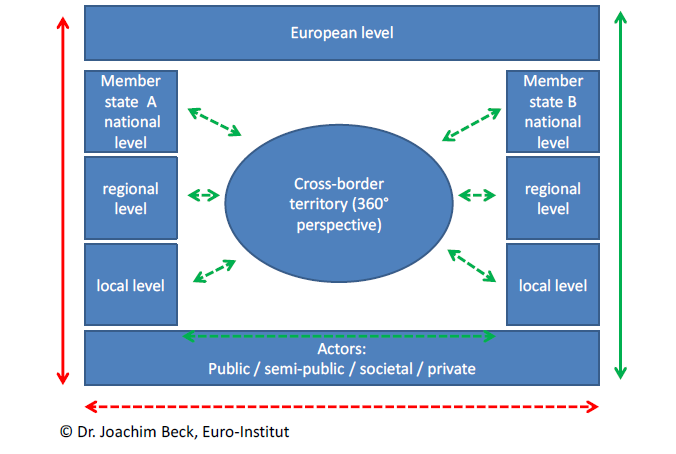

Under the new generation of the cohesion policy, the idea of evidence based policy-making has a prominent place. Cross-border territories will have to strengthen their efforts to creating and proceeding tangible impact information in the near future. This is also a prerequisite for any cross-border policy-approach that wants to become more strategic in the sense of a more focused and concentrated pattern that concentrates on the integrated development of territorial potentials (360° perspective) instead of multiplying disconnected sectorial projects.

With the Impact Assessment toolkit for cross-border cooperation, the Centre for Cross Border Studies in Ireland and the Euro-Institute have developed an instrument that can be very significant in this regard, allowing for a much more evidence based policy- and project development in the future (Tailon/Beck/Rihm 2010).

Developing a multi-level-governance based on „horizontal subsidiarity“: In the perspective of a systemic capacity-building approach it seems desirable to strengthen and enlarge the scope of action of the sub-system of cross-border-cooperation in Europe. Overcoming the seven challenges cited above would require multi-level governance that leads both to a much closer and more integrated cooperation and a much clearer functional division of labour between the different levels of cooperation. In such a perspective the EU-level would anticipate impacts of future EU-initiatives on the cross-border territories at an early stage and would allow for a better inter-sectoral coordination between the different thematic policy-areas and institutional competences which have a logical border crossing dimension. Integrated policy-making would require, for instance, standing inter-service groups on cross-border cooperation, which are them themselves interlinked with relevant groups of the Committee of the Regions and the European Council and Parliament.

The member states (and their territorial subdivisions) would on the other hand support cross-border cooperation actively and would allow for flexible solutions to be developed on the borders. This would lead to a new operating principle, which I described recently as “horizontal subsidiarity” (Beck 2012b) : Whenever a policy-field that is relevant for horizontal exchange, cannot be harmonized at the European level, member states should then at least try to setting the frame via direct coordination with their neighboring states. The term “horizontal subsidiarity” means in this respect, that with regards to cross-border policy-issues the “smaller” cross-border unit should have the possibility to solve a problem or handle a question prior to the intervention of the “bigger” national jurisdiction. This would then require that the smaller unit will become enabled by the provision of the necessary legal flexibility: experimental and opening clauses in thematic regulations and exemptions based on de minimis rules (whenever a cross- border phenomenon does not exceed a certain level of magnitude – e.g. 5 % of the population being commuters, 3% of the students studying at the neighbour- university, 2% of patients asking for medical treatment with a doctor beyond the border – an execption to the national rules will be allowed).

The local and regional actors on the other hand would have to develop shared cross-border services (Tomkinson 2007; AT Kaerny 2005) and transfer domestic local/regional competencies to joint cross-border bodies with real administrative competencies for concrete missions within relevant cross-border fields. Instead of building or maintaining relatively expensive public infrastructures separately on both sides of the border in service areas such as health, leisure time, schools, kindergarden, fairs, libraries but also transport operators, hospitals, fire department or civil protection etc., local and regional actors would develop complementary fields of specialization and share their infrastructures with local and regional actors from the neighboring state. This could give cross-border cooperation a completely new finality, allowing not only to save scarce resources but also to symbolize both the permeability and the added-value of the “joint” cross-border territory from the point of view of the ordinary citizen.

Developing subsidiarity within the crossborder-territory: In an area such as this, where there is freedom to undertake cross-border action strengthened by horizontal subsidiarity, two additional subsidiary perspectives must be taken into account. On the one hand, a vertical subsidiarity should be established within the cross-border areas of responsibility across the total spatial level (eg the total territory of the Danube macro-region, the total territory of the Lake Constance Conference, the total territory of the tri-national metropolitan region of the Upper Rhine) which would only become operative when the smaller cross-border entities (inter-municipal cooperation, Eurodistricts, EUREGIOs, etc) receive excessive demands on their pragmatic, territorial expertise. Thus, distributions of functional and specific assignments on the proficiency scale could be developed in the cross-border area which would be likely to reduce any duplication of work which has been observed, and which is still widespread today, between the different actors, institutions and territorial levels of cross-border cooperation.

On the other hand, the prospects of intersectoral subsidiarity should also be greatly strengthened. While today, in most cross-border territories in Europe, cross-border issues are primarily the responsibility of political and administrative actors (the current configuration of European aid programmes sustains this trend), subsidiary cross-border cooperation should support more strongly sectoral ownership of cross-border systems in economy, science and research, and civil society. Public action contributions would therefore be in these sectors that, in the future, would need to better arrange cross-border action amongst themselves, either in a catalytic (eg to simulate project initiatives) or complementary way (eg in the form of financial assistance to initiatives coming from these very sectors), however they should not replace them either (Grabher. 1994; Scharpf 2006) In addition to the key public cross-border assignments (infrastructure, welfare, security against risks, etc), public actors could ultimately in such a perspective, divert the justifiable functional legitimacy to act from the long-term protection mission of posterity (Böhret 1990; Böhret 1993; Dror 2002) which should be visible in the integrated approaches of a cross-border sustainability strategy.

The conceptual foundation of the interlink between the subsidiarity and the governance dimension on the one hand and the vertical and horizontal differentiation of both principles on the other are illustrated – for the case of cross-border-policy making – in the following graph:

The vertical and horizontal dimensions of multi-level governance and subsidiarity in cross-border cooperation

Promoting CBC at EU-level: From the perspective of cross-border territorial cohesion the frequently different implementations of EU law by the neighboring countries regularly leads to technical and political asymmetries, which often even reinforce structural differences rather than leveling them. It must be worrying that the comprehensive annual work output of the European Commission (on average, these are several thousand proposals for directives, policies, regulations, decisions, communications and reports, green papers, infringement procedures per year) does not explicitly consider possible impacts on the European cross-border territories so far – although it is evident how strongly they are affected by it. It therefore seems necessary that cross-border territories become more visible with regards to their specific implementation role and thus get more explicitly considered by the European policy-maker when developing key-initiatives in the context of the strategy « Europe 2020 ». In the European Commission’s impact assessment system (European Commission 2017) a specific cross-border impact category is currently still lacking. However, cross-border territories could become ideal test-spaces for the ex-ante evaluation of future EU policies. On the other hand this would require a real awareness of cross-border territories to also actively engage in this in a coordinated manner, and – for instance – present joint opinions and impact analysis throughout official thematic consultations, launched by the European Commission. It is evident, that also a joint and coordinated thematic lobbying and advocacy activity of crossborder territories should be strengthened in this regard. The European macroregions have shown how the interests of specific types of cross-border areas may well find their way into European strategies. Such a perspective of differential cross-border action based on the principles of horizontal and vertical subsidiarity appears to be a necessary prerequisite for a future capacity-building-approach, allowing for the better deployment of the potential for innovation of cross-border territories and therefore of their specific function within the context of a new horizontal dimension of European integration and the emerging European Administrative Space (Siedentopf/Speer 2002; Beck 2017b).